The Tamam Shud Case – Who Was The Mysterious Somerton Man?

- By

- February 1, 2019

- September 28, 2021

- 14 min read

- Posted in

- Conspiracy Theory Analysis, Unsolved & Unexplained

The 1948 Tamam Shud Case – sometimes referred to as The Somerton Man Case – is one of the most intriguing and truly baffling of unsolved deaths in history. Not least due to strange codes and hints at connections to international espionage. Discovered just after dawn on a Somerton Beach near Adelaide, South Australia, the deceased gentleman’s identity was a complete mystery. As was who was behind his death, which an autopsy would state was likely the administration of poison.

The Somerton Man

Bizarre discoveries upon the mystery man, as well as links to “unknown editions” of twelfth-century texts with coded messages, would baffle investigators into the strange death. As would the eerily similar death of another man in Sydney three years previously. The case still perplexes researchers into unsolved crimes and strange cases today and is regarded as one of “Australia’s most profound mysteries”. Was the Somerton Man a spy who met an unfortunate end in the dark world of espionage? Or might the circumstances surrounding his death be darker than most of us could imagine?

It is unlikely, barring the releasing of classified documents or the coming forward of an unknown witness or whistleblower, that we will ever get to the truth of this fascinating if grim encounter. However, as is the case with UFO, alien, or bizarre phenomena encounters, it is one that is essential to keep on our mental backburners. Particularly if the conspiracies and claims of connections to the dark underbelly of the international intelligence services are true. For it may aid us in spotting similar “one-off” incidents in the future.

Contents

- 1 A Grim And Perplexing Discovery On Somerton Beach

- 2 Of “Britisher” Appearance And In “Top Physical Condition!”

- 3 An “Unparalleled Mystery” With More Bizarre Twists To Come!

- 4 Inside The Suitcase

- 5 More Strange Finds At The Inquest!

- 6 A Poison “Not Accidentally Administered!”

- 7 The Tamam Shud Note

- 8 The “Code” Indentations And Unlisted Phone Numbers

- 9 Who Is Al Boxall, And Where Does He Fit Into All Of This?

- 10 Did Jessica Thomson Know More Than She Claimed?

- 11 The Equally Strange And Similar Death Of George Marshal, 1945

- 12 The Mangnoson Family Incident

- 13 H.C Reynolds Lead And Other Possibilities And Theories

- 14 A Bizarre Case With So Many Potential Avenues Of Exploration!

A Grim And Perplexing Discovery On Somerton Beach

Although they wouldn’t come forward until after the discovery of the dead body on the morning of 1st December 1948, several witnesses had unwittingly seen the man’s apparent final, pain-filled moments the previous day. At just after 7 pm on the evening of 30th November, a couple walking by Somerton beach noticed a man, dressed in what looked to be a suit, laying on the sand. He extended his right arm upwards at one point, before letting it fall back to the ground. Around half-an-hour later, another couple had the man in their sights for around thirty minutes until around 8 pm. They would later claim they did not see the man physically move, although upon looking back on occasion they thought his position may have changed at least once. Thinking he was the victim of “one too many” they left him to sleep it off.

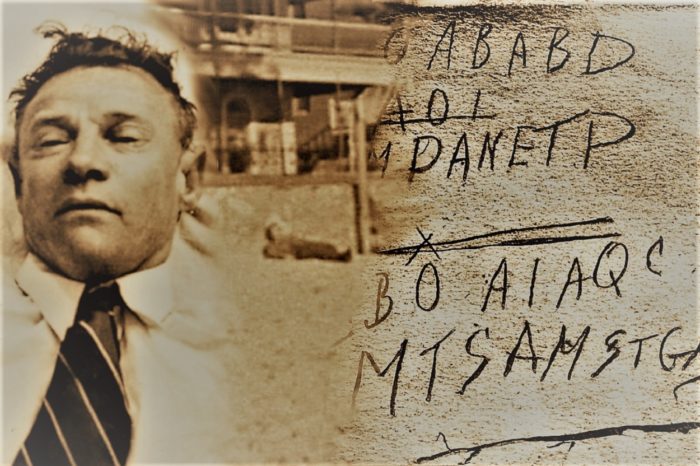

The following morning at 6:30 am police would receive a report from a member of the public, John Lyons, of a dead man on the beach. When they arrived, the man was dressed in a suit and tie, laying on Somerton Beach in the same spot, unbeknown to them at the time, where the two couples had witnessed him the previous evening.

The man lay on his back with his head resting upon the seawall as if it were a concrete pillow. An unlit cigarette was on the collar of his coat. At the bottom of his outstretched legs, the mystery man’s feet were crossed. Initially, police believe he had died while sleeping. As they would discover later, his death was far from natural causes. And, speculative as it is, the crossing of his feet very well have been the last reaction to the horrific pain very likely cutting through him.

The beach where the Somerton Man was discovered

Of “Britisher” Appearance And In “Top Physical Condition!”

Pathologist, John Burton Cleland, perhaps one of the most respected men in his field, was called in to examine the man’s body in a consulting capacity. He would determine the man to be around 40 to 45-years-old with a “more Britisher” appearance than the general population of the region and in “top physical condition”. It was further noticed that the man had no sign of having undertaken any sort of manual labor judging by the condition of his hands and nails. Perhaps of further interest were the details of his big and little toes. These would meet in a “wedge shape” and would often affect dancers or people who regularly wear pointed shoes or boots.

Although there was no “foreign substance” in the body (poison), blood was found in the stomach and there was significant congestion in the stomach, kidneys, pharynx, and gullet. And while the ultimate findings of the autopsy were “inconclusive”, Dr. Dwyer, who had performed the procedure, would state that:

I am quite convinced the death could not have been natural. The poison I suggested was a barbiturate or a soluble hypnotic! [1]

Essentially, he eludes to intentional poisoning as the reason for the mystery man’s death. Ultimately, it was the estimation of Dwyer, that the time of death was somewhere around 1 am in the early hours of the 1st December. Whether any intervention by those who witnessed him earlier in the evening would have made any kind of significant difference is impossible to say.

Furthermore, and certainly strange, every single label in every item of clothing was removed. Also of interest, particularly of the time and considering the rest of the man’s attire, he had no hat of any kind.

An “Unparalleled Mystery” With More Bizarre Twists To Come!

So strange were the details and the lack of a definite, or even likely, explanation as to the circumstances surrounding his death, the decision was made to have the man embalmed. [2] This took place on the 10th December 1948 and was the first time in Australian history that such drastic measures would take place.

Other strange details showed that of all the known dental records of any living person (at the time), none were a match for the teeth of the Somerton Man. Further still, he had no identification whatsoever on his person or in his clothing. It was as if, even before his death, he hadn’t existed at all. One further piece of information would reach the police from three witnesses who claimed to have seen a man dressed in a suit carrying another man in similar clothing along the beach front a little before the sighting of the two couples. Who this mystery man was, however, remains a mystery.

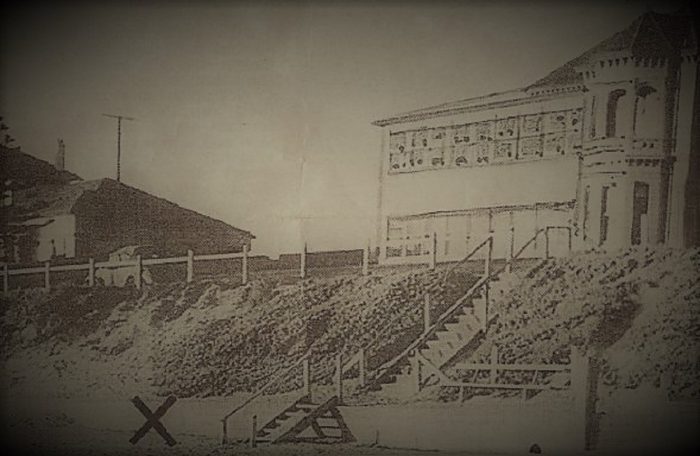

Shortly after the initial findings and autopsy results, came the discovery of a strange, brown suitcase on 14th January 1949. The suitcase came to light after staff at the Adelaide Railway Station found it had been checked into the railway’s cloakroom several weeks before at 11 am on 30th November 1948. The day before the discovery of the man’s body on Somerton Beach less than ten miles away. Intriguingly, the suitcase labels were removed, much in the same way as the labels on the man’s clothing. When police arrived to examine the case and take it into their possession, it was their belief that it belonged to the increasingly mysterious dead man from the beach.

The suitcase of the Somerton Man

Inside The Suitcase

Upon inspecting the contents of the suitcase many of the items were what one would expect to find in such a case. A pair of slippers, dressing gown, and pajamas, as well as underwear and items to shave with. There was also a pair of trousers, which whether of importance or not, would have sand in the cuffs at the bottom of each leg.

There were also several items that were not perhaps usual to your typical traveling businessman. For example, a professional electricians screwdriver. Or perhaps of more concern, a pair of scissors with purposely sharpened points, or the table knife with similar manipulations to its usually blunt blade. Furthermore was a stenciling brush, used for stenciling cargo on merchant ships.

There were also other strange discoveries. Such as a Barbour brand of orange cotton thread. The same thread was in a repair to the man’s trousers upon his body at the time of his discovery. It was a brand that was not available in Australia at that time. It would further suggest that the man had connections to the United Kingdom.

Perhaps even stranger was the discovery of several labels in the clothes that had escaped the purge of whoever removed the other labels, both on the man’s body and the other clothes in the suitcase. Investigators would speculate whether this was a purposeful act or was it a purposeful overlooking. On a tie, for example, was a label with the words “T. Keane”, while “Keane” was on a label of a laundry bag. “Kean” would also appear on a label of a waistcoat. There were also several “dry cleaning marks” [3] (codes) left on a pair of sports trousers.

More Strange Finds At The Inquest!

This information appeared promising but the dry cleaners remained elusive and no missing people of the name “T. Keane” came to light from any English speaking countries. They would, though, discover that the suitcase and the man’s coat came from the United States. As there were no import records for the coat, they would conclude that the man either purchased the coat while in America or had purchased the coat privately from an unknown individual.

Following their checking of train records on the days leading up to 30th November, investigators would narrow it down to three possible trains they believed the man had come to Adelaide on, arriving the morning of 30th November. Overnight trains from either Melbourne, Sydney, or Port Augusta. Knowing that he was cleanshaven upon the discovery of his body, investigators believed the man then shaved using the train station bathrooms, before purchasing a ticket for the 10:50 am train to Henley Beach. However, he wouldn’t board this train – although investigators didn’t know why – and instead, he would return to the station and check in his suitcase at 11 am. From there, he would likely board a bus to the Glenelg area and ultimately Somerton Beach.

In truth, the actual timeline of the Somerton Man is all speculation and theory for the most part. What we know for sure, is that by 7 pm that evening, he was laying on the sand, likely in pain or barely conscious, and likely the result of the deadly intervention of another, equally mysterious person.

A Poison “Not Accidentally Administered!”

The inquest into the bizarre death began almost immediately but then adjourned until June 1949. The aforementioned John Cleland would continue to serve in a consultancy capacity. He would, for example, speculate that even if the man were still alive when brought to the beach, a poison might have been administered elsewhere as there was no signs of vomiting near where the man was discovered. There were further theories that two such drugs that would achieve such a result would be digitalis and ouabain.

Cleland, despite his apparent private inkling that the man was intentionally poisoned, would state [4] in his report:

I would be prepared to find that he died from poison, that the poison was probably a glucoside and that it was not accidentally administered; but I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person!

Investigators would also find a packet of cigarettes. However, inside them were a different brand to the packaging, a drastically more “up-market” and expensive one. Given his belief that the man was the victim of murder, there was speculation that such a poison – that wouldn’t leave a trace or show up in the autopsy – could have been administered through the replacement cigarettes.

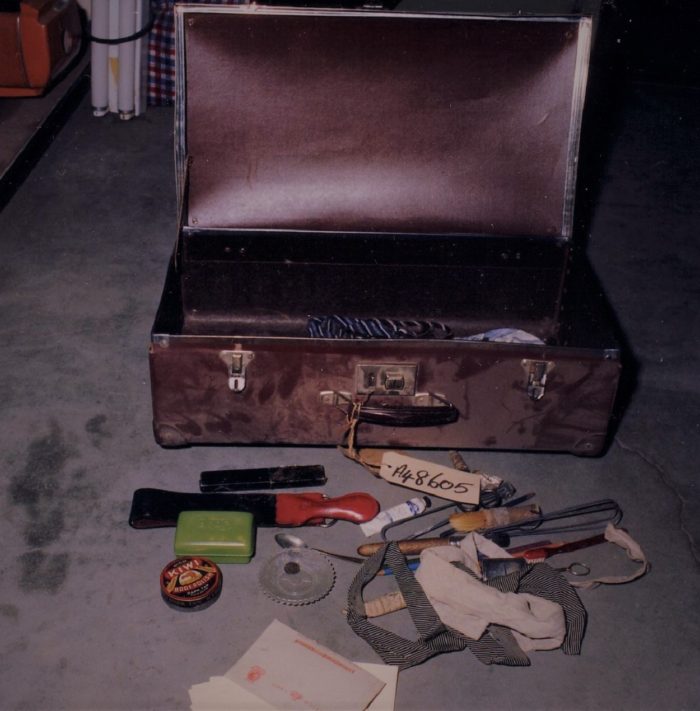

The strangest find of all, though, was a piece of paper discreetly sewn into the lining of the man’s trouser pocket.

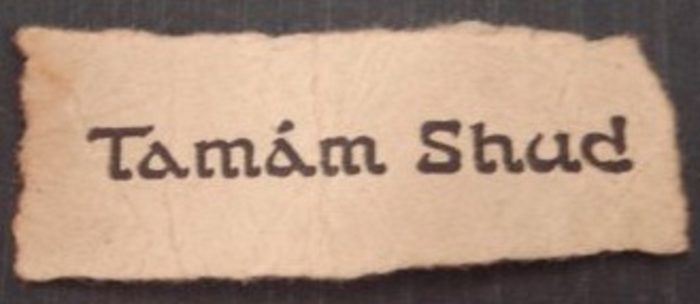

The Tamam Shud note

The Tamam Shud Note

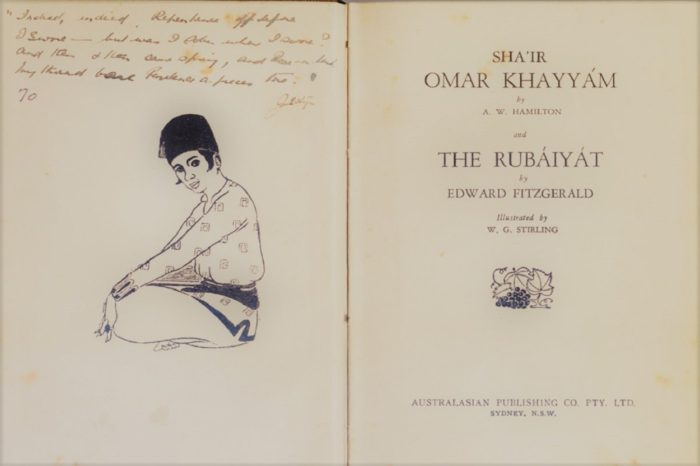

On this paper, in a particularly strange font, were the words “Tamam Shud” (you can view this in the picture above). This is the endings to a poem from Persia in the 1100s, ‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’ and translates as “it is ended” or “it is finished”. Investigators would discover that the reverse side of the page was blank. This, they hoped, would allow them to match the piece of paper up with the copy of the book from which it came. On this occasion, luck would be on their side.

On the afternoon of 22nd July, a man known only by his pseudonym “Ronald Francis” would contact police with the remarkable claim that he had the missing book they sought. According to Francis, he believed he had discovered the book in his car on the afternoon of 30th November. He had been at the Somerton Beach that afternoon and had left his vehicle unlocked. However, some reports at the time state the discovery occurred a week or two before that. Regardless, he didn’t think too much of the incident and quickly forgot it. Until seeing their public appeals for such a book, that is.

This could be an important clue. If the book, which would match identically to the one that the piece of paper in the man’s trouser pocket came from, was in the car earlier, it could be possible that he was in the area longer than on the day before his death. Or that he had made previous journeys. Or might, if we accept that the death of the Somerton Man took place against the backdrop of the conspiracy world, these discrepancies regarding the finding of the book be attempts to confuse and muddy the timelines?

The “Code” Indentations And Unlisted Phone Numbers

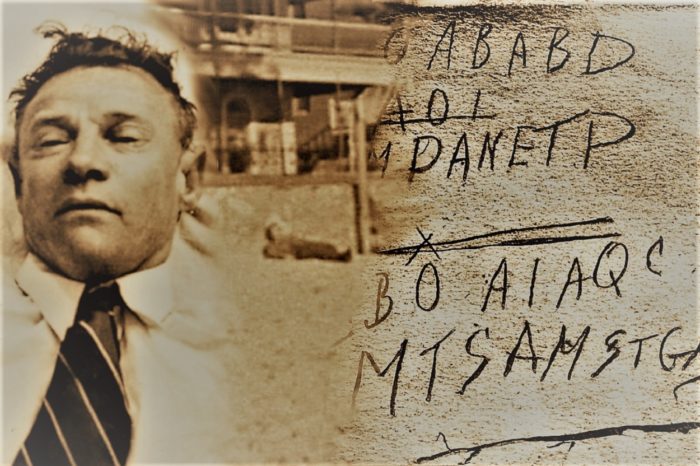

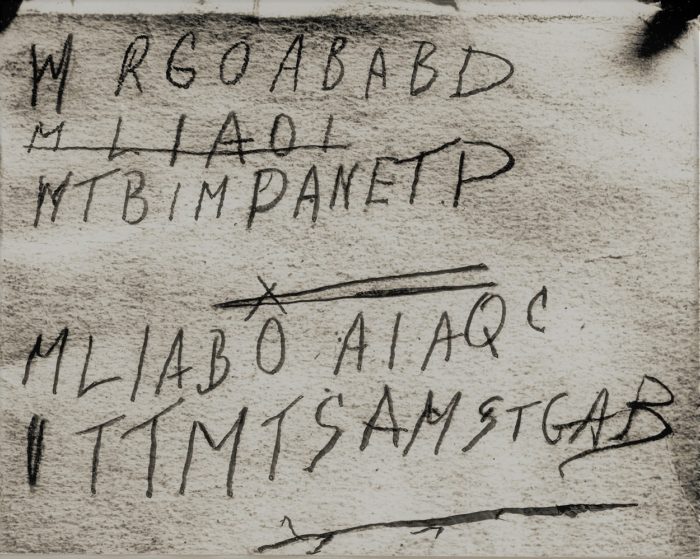

Investigators would make further strange discoveries within the pages of the book. On the back page, they would discover indentions and light ink markings of apparent random letters but what investigators would soon believe to be a code. Particularly because one of the lines had a crossing-out in error and a similar combination of letters in a line further down. You can view the picture below, however, the lines [5]

would read:

WRGOABABD

MLIAOI (crossed out)

WTBIMPANETP

MLIABOAIAQC

ITTMTSAMSTGAB!

Despite several experts in language and code-breaking examining the text extensively, most believe it will be “near impossible” to break it from the letters alone.

Perhaps even more interesting was an unlisted telephone number in the back of the book. This belonged to Jessica Thomson (who was born Jessica Harkness) and whose house was only 400 meters from the spot of the discovery on Somerton Beach. Jessica Thomson would claim to not know who the mystery man was. Or why he would have her unlisted phone number.

She would, however, make several other claims. One, in particular, that is worth examining briefly it would appear there was no real reason for her to do so. Unless, of course, these claims were signs and signals to other unknown participants in this increasingly maze-like saga.

The mysterious code

Who Is Al Boxall, And Where Does He Fit Into All Of This?

She would also claim that in 1945, during the last weeks of the Second World War, she was working at the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney. She had, at that time, a copy of the ‘Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’. Furthermore, she gave it to a soldier named Al Boxall while staying at the Clifton Gardens Hotel (remember that name is it will intriguingly come up again later). Upon finding Boxall, he indeed had a copy of the book. And on the cover, a verse 70 of the book, courtesy of Jessica (signed as JEstyn).

Interestingly or not, Boxall would elude to his involvement with army intelligence at the end of the Second World War. Right around the same time of his relationship with Jessica. Answering whether it was possible she knew of his involvement he would candidly reply “not unless some else told her”. He was, however, dismissive of an espionage connection to the Somerton Man, suggesting it was a “melodramatic thesis”. Others, though, were not.

Jessica’s behavior, for example, would suggest she knew much more than she would say. Investigators would note at the time, for example, upon seeing a plaster cast made of the Somerton Man, she was “completely taken aback”. In fact, police believed at one point “she was about to faint”. She would refuse to look at the plaster cast at all after that.

Did Jessica Thomson Know More Than She Claimed?

Furthermore, she seemed particularly interested in her name not appearing on any official record of the case. This would lead to her appearing in research and investigations under many different names. Researchers argued that this would hamper attempts to break the clues of the apparent code. At least until the late-2000s when her name became public knowledge.

Other researchers would also describe Thomson, who died in 2007, as “purposely evasive”. And would, at times, flat out refuse to answer questions on the case. In 2014, Thomson’s daughter would also publicly claim that her mother knew the identity of the dead man. And what’s more, she likely knew much of the backstory and the high-ranking people involved.

Many have suggested that she and the Somerton Man may have been having an affair. And that his death occurring coincidentally near to his speculative mistress’ home. Others, though, suggest that Thomson herself may have had intelligence involvement. And that, while again pure speculation, would suggest possible involvement in the mysterious death.

Furthermore, let’s go back to the ‘Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’ for a moment. Investigators would find Methuen would publish only five editions. Strange, then, that according to some reports the book with the missing Tamad Shud note was a sixth edition. Is this perhaps a simple error? And what is so important about this particular book of twelfth-century Persian poetry? A case three years earlier would add yet another layer of mystery to the case.

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

The Equally Strange And Similar Death Of George Marshal, 1945

This bizarre connection to an apparent edition of a twelfth-century poem that “didn’t exist” would become even more bizarre. A very similar death in Sydney three years earlier in June 1945, only two months before Jessica Thomson gave her copy of the ‘Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’ to Al Boxall at the Clifton Hotel in Sydney would share an apparent connection.

That morning, came the discovery of 34-year-old George Marshall’s dead body. He lay on his back in Ashton Park in Sydney – directly opposite the Clifton Hotel. On his chest was an open copy of the ‘Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’- a seventh edition. Marshall, incidentally, was of Singaporean descent. His brother, David Marshall would later become the Chief Minister of Singapore.

The findings would state that Marshall’s death had been a suicide by poisoning. However, there was still to be an inquest, at which several people would testify. One of them, Gwenneth Dorothy Graham, would give her evidence on 15th August 1945. On the 28th August, she was discovered dead in her bathtub, [6] naked and face down with several cuts to her wrists. Make of that what you will.

Four years later in June 1949, almost eight months after the discovery of the Somerton Man and at around the same time as the official inquest was starting, came another morose discovery that might share connections to the Tamam Shud case.

The Mangnoson Family Incident

On 6th June 1949, around ten miles from Somerton in Largs Bay, came the discovery of two-year-old, Clive Mangnoson’s dead body. He lay in a sack in the sand hills of the beach area. Beside him was his unconscious father, Keith Mangnoson, who extremely weak and confused would go to the local hospital.

This is where things begin to get strange.

Following a brief examination at the hospital, Keith Mangnoson was transferred straight to a facility for the mentally unstable. [7] He and his son had been missing for several days before the discovery. Autopsy results would fail to isolate what actually caused the young boy’s death. The pathologist, however, was certain it was not down to natural causes. He had likely been dead for around a day before his discovery.

Following these dark events, the mother of the young boy and wife of Keith Mangnoson, Roma, would report a car almost knocking her to the ground [8] outside her home. A “man with a khaki handkerchief over his face” would tell her to “keep away from the police or else”. Roma would claim categorically that it was likely because her husband knew who the Somerton Man was. And what’s more, he was about to speak about it publicly. According to Roma, the Somerton Man was Carl Thompsen, a man that Keith had worked with in the late-1930s. Interestingly or not, shortly after her report, Roma herself would collapse suddenly and find herself in hospital.

Furthermore, several other investigators would receive threatening phone calls [9] following Roma’s collapse. The secretary of the Largs North Progress Association, for example, received a call stating “Mrs. Magnoson would meet with an accident” if he continued to “interfere”. The mayor of Port Adelaide would receive three such calls.

H.C Reynolds Lead And Other Possibilities And Theories

There have been many claims as to who this mystery gentleman might be.

For example, what of the claims Jessica’s son, Robin Thomson? According to his widow, Roma, and their daughter Rachel Egan, he was likely the son of the Somerton Man. And then presented as Jessica’s and her husband, Prosper Thomson’s. They are currently seeking permission to exhume the body for DNA testing in relation to this.

In 2013, Jessica’s daughter, Kate Thomson, would appear on the television show ’60 Minutes’. She would claim her mother told her of lying to the police. And what’s more, she (Jessica) knew full well who the Somerton Man was. Further still, his identity was “known to a level higher than the police”. Rather than having an affair, it is Kate’s belief that the Somerton Man and her mother were both spies. She would state how her mother had an intense interest in communism and could speak fluent Russian. When her daughter asked where she had learned this and why, her mother would refuse to speak of it.

Perhaps one of the strangest claims would come in 2011. A woman from Adelaide would discover an ID card within her father’s possessions for a “H.C. Reynolds”. Investigators would compare a photograph of the Somerton Man with the picture on the ID card. While not exact (it was from thirty years previously in 1918) the similarities were still extremely accurate. Investigation would reveal that the ID card number (58757) would match to HC Reynolds from February 1918. In the United States. It would list his nationality as British and his age 18-years-old. From there, however, it would appear HC Reynolds simply vanishes off the face of the planet. No other records in the American, British, or Australian archives make any mention of him.

A Bizarre Case With So Many Potential Avenues Of Exploration!

What should we make of the most bizarre and fascinating case? All the details, particularly if we accept the notion that Jessica Thomson did know much more than she led authorities to believe, point towards the case emanating from the dark, double-crossing world of the intelligence services. If that is the case, then what should we make of such similar cases in the contemporary era? The bizarre death of Gareth Williams or the apparent suicide of Dr. David Kelly to name but a few. Might these too be the victims of the cold, calculating and very real assassins of the modern world? And if so, why?

Were they victims of their own side who after they no longer had a purpose? If so, what did they know too much about? The timing of the Somerton Man and George Marshall three years earlier is interesting. Might there be a connection with the aftermath of the Second World War? When the “reshaping” of the world stage was taking place in these “interim” years. Years following arguably the bloodiest conflict of the twentieth century? Might they have been victims of a foreign intelligence against the same backdrop and agenda?

Might such things happen a lot more than we think? Only unlike the Somerton Man case, do most play out behind the screens of public awareness? Perhaps it is even a possibility – if we remember the sighting of a two-suited-men, one carrying the other – that this incident was allowed to venture into the public arena? Perhaps as a very clear, while hidden from most, warning to others, whoever they may be?

The video below looks at this fascinating incident in a little more detail.

References

| ↑1 | Death Riddle of a man with no name http://www.eleceng.adelaide.edu.au/personal/dabbott/tamanshud/sunday_mail_nov2004.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Somerton Body Embalmed, The Adelaide Advertiser, December 11th, 1948 (page 3) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/43795238 |

| ↑3 | Marks may be clue to beach body, The Adelaide News, January 15th, 1949 (page 8) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/130244472 |

| ↑4 | Inquest into body found on Somerton Beach http://www.eleceng.adelaide.edu.au/personal/dabbott/tamanshud/inquest1949ocr.pdf |

| ↑5 | Coded Letters http://www.eleceng.adelaide.edu.au/personal/dabbott/tamanshud/advertiser_mar2005.pdf |

| ↑6 | Nude woman found drowned in bath, The Argus, August 27th, 1945 (page 1) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/972747 |

| ↑7 | Mangnoson Admitted To Mental Hospital, The Adelaide Advertiser, June 9th, 1949 (page 4) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36371299 |

| ↑8 | Sequel To Largs Tragedy, The Adelaide Advertiser, June 23rd, 1949 (page 9) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36373583 |

| ↑9 | Curious Aspects Of Unsolved Beach Mystery, The Adelaide Advertiser, June 22nd, 1949 (page 2) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36373373 |

Fact Checking/Disclaimer

The stories, accounts, and discussions in this article may go against currently accepted science and common beliefs. The details included in the article are based on the reports, accounts and documentation available as provided by witnesses and publications - sources/references are published above.

We do not aim to prove nor disprove any of the theories, cases, or reports. You should read this article with an open mind and come to a conclusion yourself. Our motto always is, "you make up your own mind". Read more about how we fact-check content here.

Copyright & Republishing Policy

The entire article and the contents within are published by, wholly-owned and copyright of UFO Insight. The author does not own the rights to this content.

You may republish short quotes from this article with a reference back to the original UFO Insight article here as the source. You may not republish the article in its entirety.