High-Altitude Rockets, Satellites, And Spacecraft: The Early History Of The Space Race

- By

- November 29, 2020

- September 29, 2021

- 18 min read

- 1

- Posted in

- Space, History

While today in our contemporary era there is much more corroboration in humanity’s desire to reach ever further into the far reaches of space, for a large part of the twentieth century there was very much a race to the stars involving the United States on one side and the Soviet Union on the other. Indeed, the Space Race was, in reality, another arm of the Cold War that dominated this same period.

Indeed, it is perhaps intriguing in itself that out of this ideological stand-off came the desire on both sides of the divide to out-do the other, came some of the greatest advancements in human history. It is perhaps safe to say that the Space Race was very much one of the main battlegrounds of the Cold War that would dominate the second half of the twentieth century.

However, even then, the roots of our collective desire to explore the great beyond of the Universe goes back even further than the start of the Cold War. In fact, much of the groundwork for the eventual Space Race came from the attempts of the Nazis to build “super weapons” in order to turn the course of the war – a war that was ever increasingly turning against them.

We will come back to the start of the modern space race shortly. First, though, we will quickly look at the tentative steps of reaching the stars that go back at least a century earlier.

Contents

- 1 Very Early Ideas And Proposals For Space Exploration

- 2 Germany In The 1930s – The “Birthplace” Of Modern Space Exploration!

- 3 Advanced Weapons Built Out Of A Desire For Space Travel

- 4 The “Spoils” Of World War Two – A Race To Secure The Architects Of The Eventual Space Race

- 5 “To What Victorious Nation Were We Willing To Entrust This Brainchild Of Ours?”

- 6 The Stalling And Restarting Of The Soviet Union’s Early Rocket Programs

- 7 From White Sands, To 65 Miles Above The Earth – America Peeks Into Outer Space!

- 8 Increased Feelings Of Tensions And Paranoia

- 9 The Sputnik Launch And Crisis – The Intertwining Of The Space Race And The Cold War

- 10 Further Early Soviet Successes In Space

- 11 A Connection Between The Modern UFO Age And The Space Race?

- 12 The Touch Paper Is Well And Truly Lit!

Very Early Ideas And Proposals For Space Exploration

Galileo’s discovery of Jupiter’s moons in 1610 aside, most of the early steps forward in space exploration throughout the 1800s were largely courtesy of observers from the United Kingdom or the United States.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing progressions of space exploration, however, if only in stretching the collective desire to reach the stars somewhat, was the idea from Russian, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky to build a Space Elevator in 1895.

In its most basic, the idea was for a tower to be constructed on Earth that would reach into the highest reaches of orbit – somewhere in the region of 22,000 miles above the Earth’s surface – upon which would be fixed a cable which would allow specially made “ships” to use these cables to launch themselves into space. And of course, this required no fuel of any kind.

In more recent years – and something we will examine in a future article on the history of space exploration – is that the idea, at least on the drawing board, is still being examined as to its feasibility.

Eight years later in 1903, Tsiolkovsky would arguably produce the first seriously considered proposals of how space exploration could be a reality in a work entitled The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices.

Two decades later, in the United States, Robert Goddard began developing and experimenting with liquid-fueled rockets as early as the early 1920s, eventually launching the first of its kind in March 1926 perhaps taking the first true, although very tentative steps toward the stars.

While the history of humanity’s fascination with space goes back thousands of years, and the exploration thereof several hundred years, it was only as the 1900s unfolded when such dreams began to become a potential reality. Perhaps the best place to start, then, would be 1930 in Germany.

Germany In The 1930s – The “Birthplace” Of Modern Space Exploration!

Although the pace of progress would accelerate under the Third Reich and the Nazis, German ballistic missile development was already well underway before Hitler came to power. And these missiles had suborbital capabilities. The initial goal of these early German missile development programs was to develop liquid-fueled rockets that would be able to travel a long distance and at very high altitudes.

It wasn’t long after these programs began when one Wernher von Braun, a promising engineer who had been noted as very promising, joined the project. As many know, Von Braun would eventually relocate to the United States following the end of the Second World War as part of Operation Paperclip (a mission that saw many of the German and Nazi scientists and engineers taken to America to continue their work, only this time for the US) and would eventually become one of the key contributors to NASA’s moon landings.

Von Braun would speak to the US War Department in 1947 of how he, admittedly indirectly, entered into the Nazi regime. And while there is perhaps debate as to just how involved the future father of America’s space exploration was with the Nazis, at least according to him, he was practically forced to join. He would state:

In spring 1940, one SS-Standartenfuehrer (SS-colonel) Mueller from Greifswald, a bigger town in the vicinity of Peenemünde, looked me up in my office and told me, that Reichsfuehrer SS Himmler had sent him with the order to urge me to join the SS. I told him I was so busy with my rocket work that I had no time to spare for any political activity. He then told me, that the SS would cost me no time at all. I would be awarded the rank of an “Untersturmfuehrer” (lieutenant) and it was a very definite desire of Himmler that I attend his invitation to join. I asked Mueller to give me some time for reflection. He agreed.

Realizing that the matter was of highly political significance for the relation between the SS and the Army, I called immediately on my military superior, Dr. Dornberger. He informed me that the SS had for a long time been trying to get their “finger in the pie” of the rocket work. I asked him what to do. He replied on the spot that if I wanted to continue our mutual work, I had no alternative but to join! [1]

It had been a desire of Von Braun since he was young to reach space. And his superiors’ desire for rocket-based weaponry was initially at odds with the young engineer. However, with the coming to power of Hitler and the iron grip that the Nazis had on all aspects of life in Germany, those desires were forcibly rediverted when he was made the technical director of the Nazi’s ballistic missile program!

Advanced Weapons Built Out Of A Desire For Space Travel

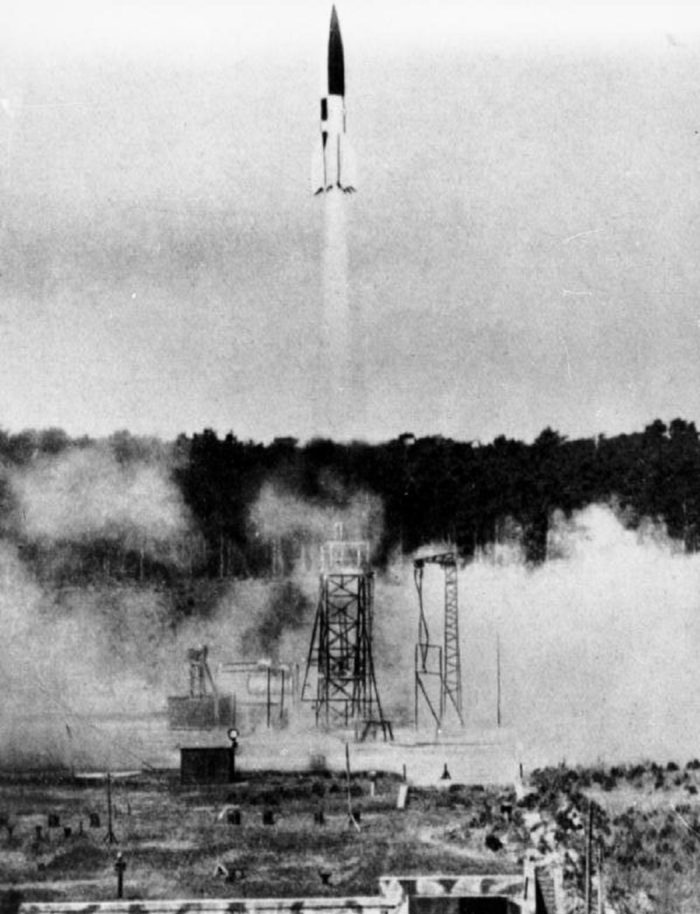

It was during this time in the early 1940s that Von Braun was part of the project that designed, built, and launched the first vehicle that reached into space – the A-4 (Aggregat) rocket. Following the test flights of the A4, it would be produced in huge numbers and undergo a name change. It would become known as the V2 (the follow-up to the already feared V1) – at the time the deadliest and most advanced such ballistic missile in the world.

Even those working with von Braun during this time were largely astounded by his apparent talents. One such technical assistant, Dieter Huzel would state in the book The Space Race: The Battle To Rule The Heavens (by Deborah Cadbury) that when he first witnessed the A4/V2 test missiles in a large hangar that they “fitted the classic concept of a spaceship”. He would continue that he simply “stood and stared…I could only think that they must be out of some science fiction film”.

It is from this deadly V2 weapon – which was launched with regularity against Allied territories to devastating effect – that both the United States and the Soviet Union would base their early rocket programs around.

In the same book, it describes the latter days of this fast-tracked rocket development – something that Hitler literally threw the last of his resources at in an effort to win the war – when it became clearer to all who were present at Peenemunde is eastern Germany as the Soviet forces got ever closer. And what’s more, in part for the treatment of Soviet citizens by the Nazis during the conflict, and in part because of the Soviet’s own propaganda machine urging its citizens that “if you do not kill a German, a German will kill you”, the Soviet Army was approaching with an “appetite for revenge”.

Von Braun, noticing how engineers and technicians were being hastily trained in what obviously would be an order to stand and defend the weapons plant, began to think of ways he could evacuate his immediate team out of the area. And this was even more so when the bodies of those who had questioned defending the plant against the Soviets were discovered hanging from trees by piano wire – often with signs on them that read “I was too cowardly to defend the homeland”.

However, von Braun also realized that such an operation – one that would involve thousands of people and their families – was one that could not be done discreetly and without attracting the attention of the SS, who surely would not think twice of treating them the same way as those who had questioned the decision to defend the plant.

What’s more, it wasn’t just the fear of fighting against the Soviets or indeed his own superiors that drove Von Braun’s desire to relocate to what he believed would soon become Allied-controlled Germany. It was the work itself, much of which was contained in the mountains of files and documentation of experiments, as well as thousands of blueprints.

And even then, as Germany was crumbling around him, Von Braun knew that these deadly weapons of the Nazis were, in his mind, the basis of how he would achieve sending humans into space. If, of course, he survived the war.

The “Spoils” Of World War Two – A Race To Secure The Architects Of The Eventual Space Race

As the outcome of the Second World War began to present itself to all involved, and with Allied Troops approaching from one side and the Soviet army approaching from the other, many of the German scientists and engineers (at least those that had such an option – and that wasn’t many), knowing full well that each respective approaching side would want to take full advantage of their knowledge and research, had to make a choice of which side they would surrender to. One of these scientists was the previously mentioned Wernher von Braun.

Of course, Von Braun couldn’t simply up and leave the weapons plant in eastern Germany – despite the fact that he had secretly discussed the benefits of surrendering to the Allies (specifically, the Americans) to his most trusted senior staff in late-1944 and early 1945 as the sounds of an Allied victory grew ever louder. However, it wasn’t until he finally received orders to relocate his team and work to central Germany that he could finally put a discreet plan in motion to ensure their surrender to the much-preferred Allies over the Soviet Union.

Part of the reason for specifically targeting the United States was the realization that they over Great Britain, for example, were in the best position to fund their research into what would become a space program as opposed to a weapons one. In fact, according to Deborah Cadbury’s The Space Race, Von Braun would state to his team following the orders to relocate their work that, “our choices are limited, but following Kammler’s order would seem to give us the best chance of putting ourselves in the way of the Americans.” [2]

From that point, while officially following orders, the main goal was to not only survive the war but to ensure their work continued in the United States.

“To What Victorious Nation Were We Willing To Entrust This Brainchild Of Ours?”

They would reach their destination in March 1945 and would immediately go about settling into the work as normal so as to keep up their pretense of obedience to the war effort. However, secretly, Von Braun and a very select few of his most trusted team were busy gathering and hiding the documents relating to their work, including private work that related very much to space travel.

Eventually, with the Allied forces only miles away, the order came to evacuate the rocket development team to the Alps (in Oberammergau), with chilling orders that their SS guards should execute them in the event that their capture was inevitable. Von Braun, though, managed to make the case for dispersing at least some of the team so that the Allied planes simply couldn’t bomb them in one go. Incidentally, many of the scientists and engineers who were transported to the Alps would be in Allied possession following their capturing of the town by the Allies at the end of April.

Von Braun would eventually make it to Austria with several members of his team. They would soon surrender to an American soldier who they happened across shortly after. Von Braun would state in a press conference of this situation by saying:

We knew that we had created a new means of warfare, and the question as to what nation, to what victorious nation we were willing to entrust this brainchild of ours was a moral decision more than anything else, we wanted to see the world spared another conflict such as Germany had just been through, and we felt that only by surrendering such a weapon to people who are guided by the Bible could such an assurance to the world be best secured!

We will move on the American side of this human divvy-up shortly (Operation Paperclip), but first, we will examine those who chose, or were simply in the eastern territories of Germany when the Soviets took control, to hand over their research to the Soviet Union. Even the previously mentioned Von Braun was a name right at the top of the Soviet’s own “wish list” of German engineers as they realized the war would almost certainly end in its favor.

Indeed, while Von Braun was relocating his team and their families to central Germany in the hope of avoiding the suspicions of the SS, each of the American and Soviet intelligence services were attempting to get to him first before the war ended.

Following the end of the war in Europe, arrangements were made by both the Americans and the Soviets to move their captured scientists to their own territories. It was, indirectly, off the back of these arrangements that the seeds of the Cold War were perhaps sewn. With each side wanting to beat the other. And while at first this race for technological muscle-flexing revolved around nuclear weaponry and far-reaching missiles, it soon developed into a race to reach the stars themselves – the Space Race.

The Stalling And Restarting Of The Soviet Union’s Early Rocket Programs

While it would appear – in retrospect – that the United States managed to grab the best of the scientific and engineering talent from the Nazi spoils, the Soviet Union would embark on their own missile programs. And, like the United States, these would soon develop into attempts to reach into outer space.

What is perhaps interesting is that only a decade and a half earlier, the talent of the Soviet scientists and the progress they had made was at least in line with those of the Germans. However, following the Great Purge of Stalin in 1937 which saw huge repression of political opponents and those who didn’t share in the Soviet ideology, this progress was almost halted. And certainly did not recover in any significant way until the end of the Second World War. And only then when they gained access to the work of their German counterparts.

In some respects, the fact that the center of German rocket development was in the eastern part of the country in Peenemunde, played very much into the Soviet’s hands. And not just in securing the services of Nazi scientists. Furthermore, on the orders of Stalin, they also managed to plunder numerous V2 parts and tools from the plants themselves.

The Soviet Union would spend more than a year at the location before finally moving these parts and the German scientists now under their control to a location around 150 miles outside of Moscow at Gorodomlya Island near Lake Seliger as part of Operation Osoaviakhim (essentially the Soviet version of Operation Paperclip).

Interestingly, the leader of these Soviet engineers (essentially, the Soviet equivalent of Von Braun) was one Sergei Korolev, a man who had fallen victim to Stalin’s Great Purge only to now find himself the chief rocket and spacecraft engineer for the Soviet Union. Indeed, by contrast to his American counterpart, Korolev was unknown to the world – both in the west and within the borders of the Soviet Union until his death in the mid-1960s.

The Soviet authorities would refer to him as the “Chief Designer” and would have KGB agents follow him everywhere he went. This was to officially protect him from assassination or kidnap by the west. However, it would seem that at least part of the reason for the round-the-clock surveillance of Korolev was to ensure that he spoke to no one of the secrets of his work.

Under Korolev’s leadership, the Soviets would essentially reverse engineer the V2, eventually resulting in the R-1 rocket only three years after the end of the war in 1948. The race to the stars through the desire to replicate such advanced Nazi weaponry was well and truly underway.

From White Sands, To 65 Miles Above The Earth – America Peeks Into Outer Space!

Of course, scientists in the United States – both American born and transplanted German ones – wasted little time in going to work and developing the technology of the Nazis. In fact, not only had they managed to secure the services (in return for American citizenship) of a great number of the leading German scientists and engineers, they had also taken around 100 V2 rockets back to the United States. This would put them even further in front of the Soviet Union.

Most of those who arrived in the United States as part of Operation Paperclip would, at least initially, be based at the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, including Werhner von Braun. And much like their Soviet counterparts, they immediately went about reconstructing and improving on the Nazi V2 rocket and ultimately performing test launches of them.

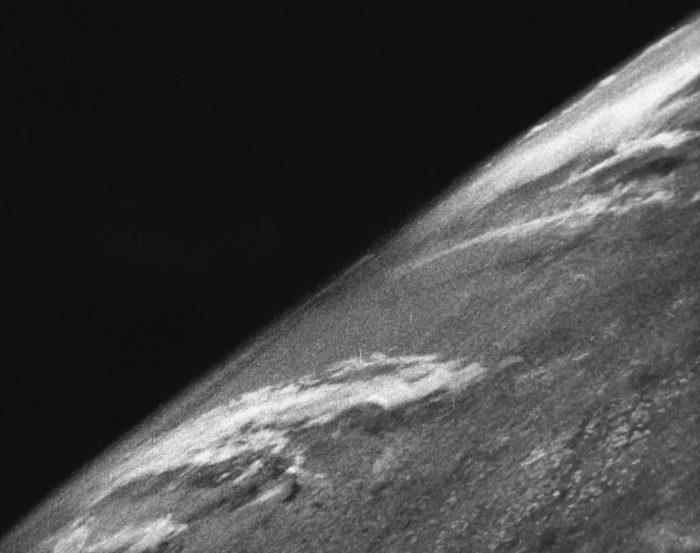

In fact, through the United States’ efforts and test launches, the first picture of the Earth would be taken during the V2 No 13 launch on 24th October 1946 (less than a year after the end of the Second World War). The launched rocket reached an altitude of around 65 miles with the picture being captured with a DeVry 35 mm motion camera. You can see that picture below.

We should note that although this was the first picture captured of the Earth, the V2 No 13 was not the first “spacecraft” to leave Earth and enter space. While working in eastern Germany for the Nazi regime, Von Braun had overseen a V2 rocket launch (MW 18014) carried out on the 20th June 1944 which had reached an altitude of just short of 110 miles.

These one-time Nazi engineers would also develop the first two-stage rocket in 1949 before Von Braun and his team were relocated to Fort Bliss in Huntsville, Alabama where they would work at the Redstone Arsenal. It was from this location during the 1950s that the first Redstone rocket was developed. And while it was developed as a ballistic missile, the rockets that followed from this initial design would play a crucial role in launching the United States into the space race.

Increased Feelings Of Tensions And Paranoia

As the 1950s began to unfold, it became clear that what would become known as the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union was very real, even if at the time it was nothing more than increased feelings of tension and paranoia from each of the respective populations. The Americans, though, continued to have measured successes as the decades changed over.

In February 1947, for example, they succeeded in sending the first animals into space when fruit flies were sent in a V-2 to just short of 70 miles. They were placed in a specially built capsule which was then ejected, making it to the ground with the deployment of a parachute. The flies, incidentally, all survived the experiment (which was to test the effects of radiation exposure at high altitudes).

They would repeat this but on a larger scale when they sent a rhesus monkey into space in June 1949 (it was the second such test with a monkey – the first of which failed). Although the test was a success the second time around, the unfortunate monkey did not survive the landing when the parachute attached to it failed to open. The United States would perform several such test flights with monkeys – most of which did not survive them.

However, in the Soviet Union, their own space program would suddenly burst onto the world stage with a success even greater than those of the Americans. In fact, we might argue that the space race as we understand it today, began for real in the summer of 1957 when the Soviet Union launched the first intercontinental ballistic missile.

The Sputnik Launch And Crisis – The Intertwining Of The Space Race And The Cold War

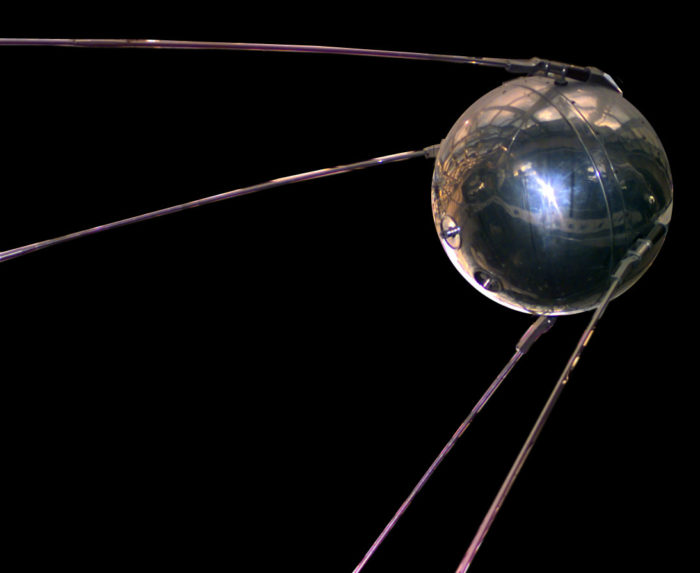

After the initial American successes, the Soviet Union appeared to take large leaps ahead following the R-7 mission. Only several months later, for example, they succeeded in launching Sputnik 1, the first satellite into space on 4th October 1957.

In keeping with the constant tit-for-tat nature of the Cold War, it might be argued that the drive to place the first satellite in orbit for the Soviets came when the President of the United States (at the time), Dwight Eisenhower, made a public promise in July 1955 that America would look to launch an artificial satellite into the Earth’s orbit. Only days later, the Soviet Union made an almost identical announcement.

The years of preparation finally culminated in the launch of the satellite – which was essentially a metal sphere just short of 60 cm across with four radio antennas attached to it. From these radio antennas, signals could be sent back [3] to Earth. The satellite would spend a total of three weeks in orbit before finally going silent due to battery failure. It would eventually fall back to Earth several months later. The mission, though, had been a resounding success, something that the media platform of the world wasted no time in announcing to their respective populations.

Whether it was the Soviet’s intention or not, as soon as the world became aware of the success of the Sputnik launch there was a feeling of distress within the governments and the populations of the United States, as well as other countries in western Europe. If, for example, the Soviets had the technology and the knowhow to send a satellite into space to orbit the planet, then they could, potentially, strike America and her allies with equally advanced (and likely nuclear) weapons.

The American authorities, due to their U-2 spy plane missions, were already beginning to notice data that suggested the Soviets were beginning to move ahead of them in nuclear powers – which would include in the race to get to space. The launch of the Sputnik satellite only appeared to prove these fears. And more importantly, took those fears into the public arena.

Newspapers would write articles on the successful satellite launch of the Soviet Union and what it might mean for the average American almost daily, which only served to increase public anxiety further.

It was from this incident and the public fallout in the west that the space race and the Cold War truly became intertwined. And what’s more, this early and, to some, shocking success was quickly followed by further successes that only increased the tension and indeed the stakes even further.

Further Early Soviet Successes In Space

Following the launches of the Sputnik satellites, it became clear to all with an interest that the Soviet Union had its sights much further than just above the Earth. In fact, the next success came only a month after the launch of Sputnik 1. And this time, rather than just sending a satellite into orbit to send radio signals back to Earth, Sputnik 2 would feature a cabin that would take a dog – Laika – with it, the first time a living animal was put into orbit.

Incidentally, Laika died after only several hours in orbit, although this information only surfaced following the collapse of the Soviet Union, with the original claims being that she had survived for around a week.

Beginning in January 1959 the Soviet Union would embark on their Luna missions with the launch of Luna 1. Although it failed in its main objective to reach the Moon, it was still the first spacecraft to escape the gravitational pull of the planet and became the first artificial object to be put into a heliocentric orbit. It would miss its target of the moon by a considerable distance due to a malfunction that resulted in an error to the upper stage rocket’s burn time. The mission was also important in discovering further information about the Van Allen radiation belt.

Around nine months later, though, The Soviet Union would launch Luna 2. And this time, the mission was much more successful. Launched on 12th September 1959, the object became the first spacecraft (albeit unmanned) to reach the Moon, and ultimately another world, just over a day later.

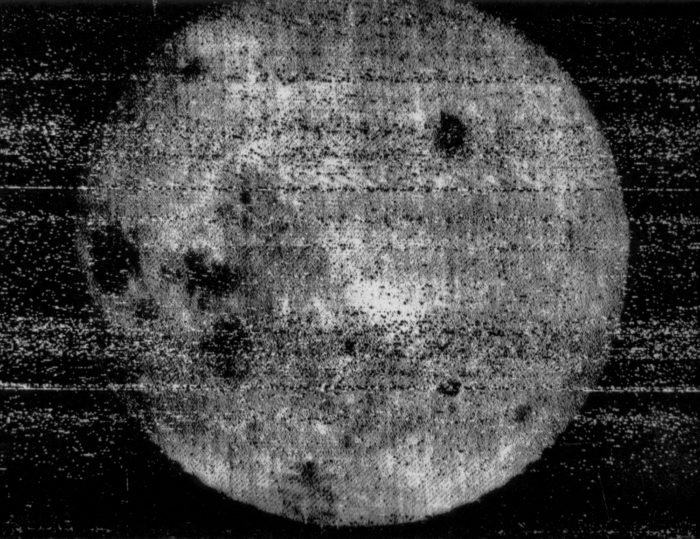

Less than a month after the success of Luna 2, Luna 3 was launched. This time, rather than land on the Moon itself the probe was sent to the far side of the celestial body. It would capture the first-ever photographs of this previously unseen side of the Moon providing scientists and researchers with a wealth of information.

Needless to say, if the Sputnik missions had created a sense of fear and even panic in the minds of the west, the fact that the Soviet Union had now reached the moon did nothing to calm such concerns. The Soviet Union, meanwhile, enjoyed bragging rights on the international stage.

A Connection Between The Modern UFO Age And The Space Race?

Whether there is a connection between the beginning of the modern UFO age and the start of humanity’s own collective efforts to reach the stars is perhaps something open to debate. However, the fact is that as sightings of apparent vehicles from other worlds in the Earth’s skies began to stack up around the world, the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union began to increase their efforts to reach space.

It is certainly an intriguing thought that there is such a connection between the two. After all, it is the belief of many that the destruction of the Second World War, including the nuclear destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in the summer of 1945 (not to mention the small plethora of nuclear tests that proceeded and followed it) is part of the reason for this seemingly extraterrestrial interest in our planet. And that interest increased even more – at least according to some researchers – when humanity’s attention turned toward conquering space.

While such notions are bordering on preposterous for some, they are most certainly worth considering and make a certain amount of sense. If there was an advanced (and peaceful) spacefaring civilization out there in near or far reaches of space, perhaps even several, it would make sense, for example, that they should ensure that a warlike civilization (and make no mistake, that is what humans are) should at least be supervised in their efforts to escape the limits of their own world and reach into the endless possibilities of the Universe.

Another possibility, though, is that these “alien crafts” may very well have been experimental aircraft of these newly moved German scientists and engineers. And while the notion that UFOs are simply top-secret advanced aircraft of the American military is nothing new, it is perhaps intriguing that such incidents as the Roswell crash occurred in the same (relative) part of America where the people of Operation Paperclip were initially working from. Not to mention that the Modern UFO age began at almost the same time as the aforementioned scientists arrived there.

Maybe there is a connection to the Cold War itself. After all, both sides of the ideological divide often suspected these strange objects were top-secret aircraft of the other. Although each side would ultimately claim they were not behind such strange objects (following several close-calls of strange objects almost leading each side to “retaliate” against the other), it is not at all a stretch of the imagination to think that at least some of the sightings might have been such secret advance military vehicles.

These ideas and suspicions are ones that we will come back to as we walk through the story of the space race, and as we examine the small plethora of UFO sightings by those who ventured out into the great beyond.

The Touch Paper Is Well And Truly Lit!

The 1950s began with each nation believing there was a possibility that space travel might be achievable. Now, as the 1960s awaited and with the successes of the decade there for all to see, those dreams were much closer to being a reality.

As the 1960s began to unfold, it would become increasingly obvious that the race to reach the stars was of great importance to both the authorities in the United States and the Soviet Union. And while the Soviets certainly landed the first early blows in the Space Race, as the new decade continued, the American’s NASA would eventually land the first knock-out shot when American astronauts reached the Moon.

The moon landings certainly didn’t end the space race, though. As we will see, each nation turned their attentions much further afield with missions to other planets. And these missions played out with varying levels of success for each nation, as the Soviet Union would attempt to reach Venus while the United States set their sights on Mars.

We will examine the programs and missions that led to the eventual Moon landings, as well as the missions to Venus and Mars that followed very shortly in a future article. And while those strides will perhaps prove to be a little more exciting than the early years of humanity’s efforts to reach to stars, without those foundations – unwittingly put in place during the bloody carnage of the Second World War – the achievements that would follow would not have been possible.

Indeed, in a world where the most unlikely connections surface, it is an intriguing thought that out of such destruction could come one of humanity’s greatest collective achievements.

The video below looks at these early years of the space race.

References

| ↑1 | Von Braun’s 1947 explanation to the US War Department regarding his involvement with the SS |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Space Race: The Battle to Rule the Heavens, Deborah Cadbury, ISBN 9780007 209941 |

| ↑3 | Sputnik and Amateur Radio https://web.archive.org/web/20071011045828/http:/www.arrl.org/news/features/2007/09/28/03/?nc=1 |

Fact Checking/Disclaimer

The stories, accounts, and discussions in this article may go against currently accepted science and common beliefs. The details included in the article are based on the reports, accounts and documentation available as provided by witnesses and publications - sources/references are published above.

We do not aim to prove nor disprove any of the theories, cases, or reports. You should read this article with an open mind and come to a conclusion yourself. Our motto always is, "you make up your own mind". Read more about how we fact-check content here.

Copyright & Republishing Policy

The entire article and the contents within are published by, wholly-owned and copyright of UFO Insight. The author does not own the rights to this content.

You may republish short quotes from this article with a reference back to the original UFO Insight article here as the source. You may not republish the article in its entirety.

1 Comment

UFO Insight does not take responsibility for the content of the comments below. We take care of filtering profanity as much as we can. The opinions and discussion in the comments below are not the views of UFO Insight, they are the views of the individual posting the comment.

Newest comments appear first, oldest at the bottom. Post a new comment!

The 1965 Kecksburg case was a GE Mark 2 re-entry vehicle used to spy on Russia. Google our research paper.