The Realm Of The Gods: The Apollo Program, The Moon Landings, And A New Dawn

- By

- December 31, 2020

- September 29, 2021

- 22 min read

- 1

- Posted in

- Space, History

Following the success of the Gemini missions, the United States found themselves ahead of the Soviet Union in the race to reach the moon. They would soon turn their full attention to the Apollo missions – the program that they felt confident would achieve their lunar goals.

During this time, the Soviet Union would continue its efforts to reach the moon first. However, behind closed doors, the Soviet Space Program was far from the slick machine it had once been at the start of the 1960s. Political change (at least in terms of budget priority), as well as in-fighting on which direction the program should go, had severely weakened it. So much so, that the United States were much further ahead than even they realized.

And while the Apollo missions began with a disastrous and fatal accident, it would eventually flourish into the program that would win the Space Race for the United States.

Contents

The Apollo Program – The Realization Of Reaching The Moon

Following the disaster of the Apollo 1 test, the United States seemingly steadied their resolve and proceeded with a quiet determination to come out on top of the Soviet Union. However, the fatal incident had severely shaken NASA to the core, in particular why it had happened in the first place. [1] An investigative team was assembled to look into this, tracing each part of the Apollo 1 timeline, right down to every individual part.

The findings, unofficially at least, were largely based on the persistent prodding from politicians to hurry their efforts to beat the Soviet Union. In part, because of this, there was no overall regularity body. Each department simply worked to their own standards and with their own preferred suppliers and materials. Essentially, there needed to be more communication and a general NASA standard.

Although this overhaul of such standards would take some time, by October 1968 Wally Schirra, Walt Cunningham, and Don Eisele sat in the Apollo 7 on top of a Saturn 1B rocket preparing for launch – on the very same launch pad at the Cape Kennedy Air Force Station that witnessed the tragic Apollo 1 disaster. There had been several unmanned test missions in the 18 months since the fire, but this was the first Apollo mission to feature crew.

Unlike previous crewed space missions, the Apollo vehicle was designed so that the crew could safely detach themselves and move around the cabin. There was even a separate area – albeit cramped – where astronauts could have a moment to themselves and away from mission control and, in turn, the eyes of the general public.

It was to be an 11-day mission and was generally designed to test the space of the cabin and the interaction of the crew themselves in such an environment. After all, if NASA was to reach the moon, they would have to survive, and cope, with such conditions for a prolonged amount of time.

Ultimately the mission was a success, despite each of the crew suffering from flu for the majority of the mission. Two months later, the next Apollo mission would truly capture the American and the world’s attention.

The short video below examines the Apollo 7 mission a little further.

Apollo 8 – Where No Other Human Had Previously Gone!

Although the crew of the Apollo 8 wouldn’t land on the moon they would become the first humans to orbit around it, seeing for themselves close-up a side of the moon that we on Earth never get to see. And what’s more, the 6-day mission would take place during Christmas 1968, perhaps adding a little more drama to the already momentous occasion, something that would be reflected in (at the time) the largest television audience in history.

The Apollo 8 launched on the 21st December from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station with Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders on board. Rather than merely orbiting the planet, however, they began moving away from it.

Just before Christmas Eve, Apollo 8 was approximately halfway between the Earth and the moon. As they stared back at their home planet, they could see it in its true, entire beauty. In fact, it is from this mission that the iconic picture of the Earthrise was captured (by Anders, while in lunar orbit) – you can see that picture below.

The astronauts would describe to mission control, as well as the television audience, not only what they were seeing, but what the television audience themselves were looking at. Although the feeds were live, they were still carried in black and white, meaning they even had to describe the colors of the planet. Remember, this was at a time when most people had very little idea of how the Earth truly looked from space.

Jim Lovell, for example, would describe to the television audience how the colors of “the waters are all sorts of royal blue”, while the clouds were “bright white”. He would then describe the land areas as “generally brownish to light brown in texture”. However, perhaps one of the most thought-provoking things Lovell said to the television audience thousands of miles away in space was:

What I keep imagining is if I’m some lonely traveler from another planet, what I’d think of Earth at this altitude…whether I’d think it would be inhabited or not!

An intriguing thought indeed – perhaps especially so as humans themselves (at least through the astronauts) were now an albeit tentative space-faring race.

It was shortly after this when Apollo 8 crossed the equigravisphere, meaning they were now within the dominating pull of the moon’s gravity as opposed to the Earth. With their destination now around 40,000 miles away, they would soon have their chance – assuming there were no surprise errors or setbacks – to circulate around our celestial neighbor in its orbit.

Into Lunar Orbit

As Apollo 8 approached its celestial destination the three crew members became increasingly alert to the final decision as to whether they were to go into lunar orbit or merely perform a flyby and head back to Earth. They would await that decision from Houston who was monitoring every aspect of the mission.

The specifics of every decision had to be precise in the extreme. For example, if the decision was made to enter lunar orbit, the Apollo 8’s engine had to operate at maximum power for an exact 247 seconds, after which the astronauts themselves would guide the craft with their altitude control thrusters. If this exact time was not adhered to the Apollo 8 would simply continue past the moon unable to return to Earth, or it would simply smash into the lunar surface. Perhaps ironically, if the thrusters outright failed, the Apollo 8 would be presented with the safest scenario in that it would simply circulate the moon and head back to Earth naturally.

As decision time approached, everything appeared to be “go” from Houston’s perspective. When the decision finally came with mission control informing the astronauts that they were “go all the way”, Lovell replied, “we’ll see you on the other side”. Then, Apollo 8 went out of communication as it ventured to the dark side of the moon and into lunar orbit.

Descriptions Of The Dark Side

Although Apollo 8’s attempt to enter lunar orbit had been a success, back in Houston, and indeed in homes across the United States, people were left on the edge of their seats wondering just what had happened.

After waiting and waiting, checking the clock to see how many minutes had passed by, Jim Lovell’s voice came over the speaker, “Go ahead Houston!”

The many people at mission control erupted into a cacophony of applause and cheers as the realization that the orbit attempt had been successful. It was a scene that was likely, albeit much more reservedly, played out in many homes across America.

However, after the cheers and applause had died down, the nation listened eagerly for the astronauts to describe to them what they were seeing – what was the moon like close-up? Lovell would state that it was “essentially gray, no color”, further describing the surface as being “like plaster of Paris or a sort of grayish beach sand”. He would state that as he looked at the Earth, it appeared as a “grand oasis in the big vastness of space”, further stating that “the vast loneliness is awe-inspiring, and makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth”.

Borman, on the other hand, would state that the moon was a “vast, lonely, forbidding place, an expanse of nothing (like) clouds of pumice stone”.

The crew would spend the rest of Christmas Eve orbiting the moon while taking hundreds of photographs of the surface in an attempt to locate an ideal landing site for the landing attempt of one of the future Apollo missions. Following this, on Christmas Day, Apollo 8 would begin back in the direction of Earth. Much like entering the orbit, the precise timings and lengths of the thrusters were key. And once again, everything went according to plan as Apollo 8 began the almost 60-hour journey back home.

They would splash down into the Pacific Ocean just off the coast of Christmas Island before being recovered and taken safely back to the United States.

The video below looks a little further at the Apollo 8 mission.

The Misperception (And Unraveling) Of The Late-1960s Soviet Space Program

While the Apollo missions were unfolding, the Soviet Space Program was, in reality, floundering. They had switched their attention to the N-1 rocket that they believed would propel them to the moon before the Americans – if only by achieving lunar orbit. This was also, in part, a result of the tragic death of Vladimir Komarov during the Soyuz 1 mission.

The United States’ intelligence agencies were certainly concerned enough to order several reconnaissance missions over the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Indeed, the N-1 rocket was seemingly larger and more powerful than the United States’ own Saturn V. What’s more, following the successful launch of a Zond with tortoises, flies, and worms which went around the moon and back, the intelligence agencies in the United States believed this was a precursor to a manned flight to our orbiting celestial body.

In reality, it was the intention of the Soviets to carry out several more test flights before even thinking of sending a crew to the moon. Nevertheless, it was these developments in the Soviet Union that spurred on the Americans to send the Apollo 8 into lunar orbit during the Christmas holiday of 1968.

Indeed, the decision was very much a gamble and faced some resistance internally from some quarters as a risk too great. However, the move is a good example of the intense desire of each side to “win” the Space Race, and in turn, a round of the Cold War. It is perhaps also worth considering that the mission would be the last under Johnson’s administration before he handed the keys of the White House over to Richard Nixon.

However, following the success of the Apollo 8 mission, intelligence agencies began to believe that the Soviet Union was about to make an attempt to land cosmonauts on the moon in an effort to outdo their own lunar orbit achievements.

Any hope the Soviet Union might have had, though, seemingly vanished entirely on the afternoon of 21st February 1969 during an unmanned test mission of the N-1. Almost immediately after beginning to rise upwards errors began to occur and engines shut themselves off. Several moments after rising into the sky, with further errors and overheating occurring throughout the rocket, the N-1 burst into a huge ball of flames sending wreckage hurtling back to the ground.

For the Soviet Union came the harsh and final realization that the United States had won the Space Race. Even though they had not managed yet to land a person on the moon itself, they achieved lunar orbit with a crewed space vehicle. And with a landing now only a matter of time, it was unrealistic, even for the most ardent believer in the Soviet Space program that they would manage to send Soviet cosmonauts to the lunar surface any time soon.

Destination Moon

Although it was decided that Apollo 11 would be the mission that would attempt to land on the moon (even the crew of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were decided), there was still the issue of testing the actual landing module. The first of these tests would be undertaken by the crew of the Apollo 9 mission.

On the 3rd March 1969, at a little after 4 pm, Apollo 9 launched on its way into Earth orbit for its 10-day mission with the landing module on board. Once in orbit, the crew of James McDivitt, David Scott, and Rusty Schweickart would perform as many of the tasks and maneuvers as possible that the Apollo 11 crew would.

These tests would begin on the fifth day of the mission. After docking with the moon taxi, McDivitt and Schweickart would enter the docking tunnel as they made their way to the landing module. Staying in the Apollo was Scott.

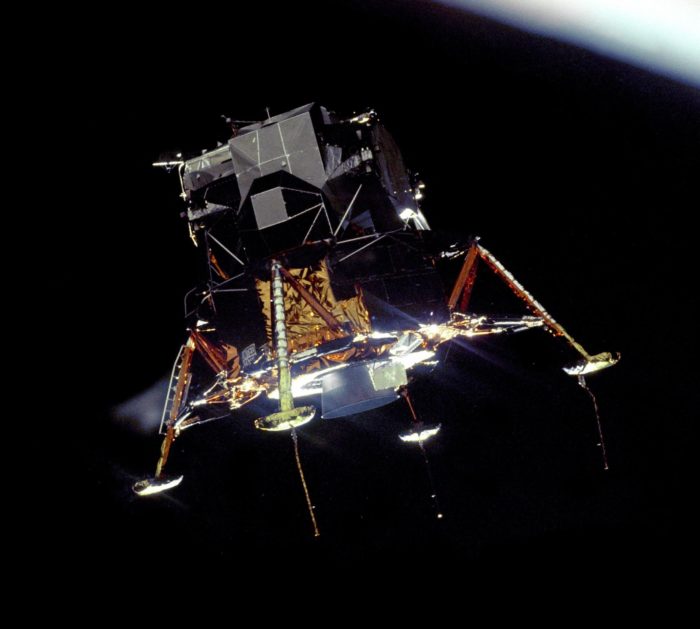

They would eject the spider-like vehicle (hence its nickname Spider) from the Apollo and took control of the specially made space vehicle. They would, however, remain within close proximity of Apollo 9 in case of any errors or failures with the landing module. If, for example, they became trapped and unable to power the vehicle, the Apollo spacecraft would make the short journey to them and come to their rescue. Eventually, though, as the first tests went by with no hitches, the two astronauts would take the landing module a little over 100 miles from the Apollo 9 craft.

After these tests were all but complete (all of which were a success), and after six hours away from Apollo 9, the pilots would jettison the “legs” of the Spider, and then using the thruster engine would guide itself back to the Apollo. The docking was also a success, and the two pilots returned to Apollo 9, which would remain in orbit for a further five days as per the length of the upcoming lunar landing mission.

The short video below examines the Apollo 9 mission a little further.

The Final Dress Rehearsal

A little over two months later, on 18th May, Apollo 10 launched on what would be the final dress rehearsal of the lunar landing missions. Onboard were Thomas Stafford, John Young, and Gene Cernan, who would embark on the eight-day mission to orbit the moon and perform as many of the landing module tasks as much as possible meaning they would all but actually land on the surface, instead remaining around eight miles above the moon itself.

Upon reaching lunar orbit, Stafford and Cernan would enter the landing module and detach from the Apollo with Young remaining in orbit around the moon. The two astronauts would then operate completely independently of the Apollo and begin their descent. As they did this, it not only tested the descent engine in relation to the moon’s gravity, it also allowed to ensure the landing radar operated as it should – something that would obviously be crucial to the next Apollo 11 mission.

The near-landing also gave the two astronauts piloting the landing module the chance to survey the Sea of Tranquility – the proposed landing site of Apollo 11. Following this, with all of the tests having proven successful (aside from a sudden roll of the module that temporarily stopped hearts at Mission Control as they listened to the pilots correcting their error and regaining control), the descend stage was sent away which then powered itself back to the Apollo, just as the Apollo 11 would only two months later, only from the actual surface of the moon.

Shortly after having performed 31 orbits of the celestial body, the Apollo 10 set off back to Earth, eventually splashing down in the Pacific Ocean near American Samoa before being recovered by a US Navy vessel.

With the mission a resounding success, and as many of the questions answered, the time was upon NASA to bite the cosmic bullet and send Apollo 11 to attempt to land astronauts on the moon itself.

Incidentally, the Apollo 10 mission was the first that would send live transmission in color back to Earth.

The short video below looks at the mission of Apollo 10.

The Moon Landings – The Ultimate Prize Of The 1960s Space Race

On the afternoon of 16th July 1969, Apollo 11 would launch on what would be the most historic achievement of the twentieth century, perhaps ever. Onboard were Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins.

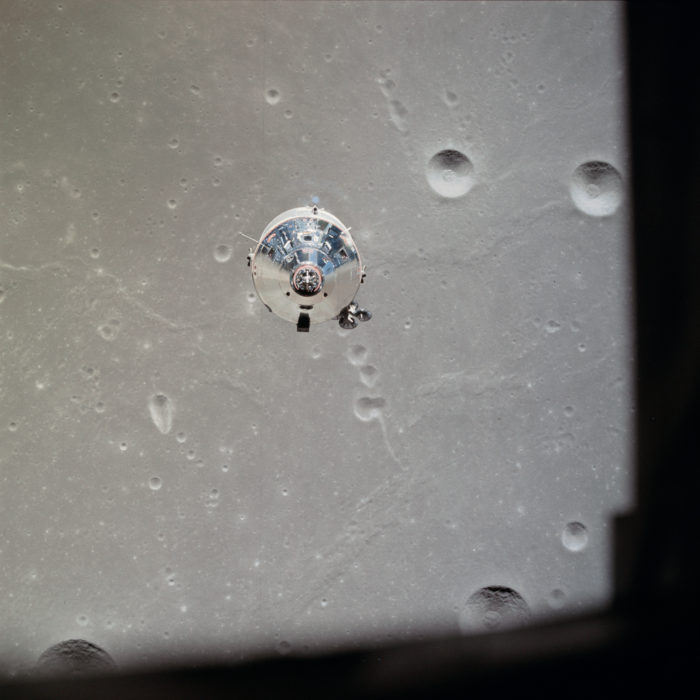

The Apollo 11 was essentially three different vehicles. The command module, a service module, and the landing module.

After three days of traveling away from the Earth, the Apollo 11 successfully entered into lunar orbit. Shortly after, Armstrong and Aldrin would make their way toward the lunar module (nicknamed Eagle) while Collins remained in the command module. They would detach themselves from the main craft and begin their descent to the moon’s surface.

As they did so, however, the two astronauts noticed they were slightly ahead of their schedule in terms of what they could see meaning they were traveling faster than had been anticipated. This, in turn, would mean they would land several miles outside of their target area. However, a short time later, Armstrong, Aldrin, and the entire mission control would seemingly have even more pressing concerns.

“If It Does Not Occur Again, We Are Fine!”

The Eagle’s onboard computer system began to flash warnings, which Aldrin relayed to mission control. These were “12-02” and 12-01” warnings and suddenly all attention turned to the Guidance Officer Steve Bales, someone referred to as a “genius” within the walls of NASA’s mission control. He monitored the systems closely from Houston and declared that it was “executive overflow” and that “if it does not occur again, we are fine”.

Essentially, due to the sheer volume of tasks the onboard computer was being asked to do, it had to place some of them on the back burner and come back to them. It was an intentional decision of prioritizing the tasks that were of more urgency. In short, it was doing exactly as it should in just this situation.

The Director of Apollo Flight Control Programming, Margaret Hamilton perhaps summed it up best when she stated in Datamation magazine that “to blame the computer for the Apollo 11 problems is like blaming the person who spots a fire and calls the fire department”. She would elaborate that by reprioritizing the lower tasks over the more urgent ones “rather than almost forcing an abort, (the computer) prevented an abort”.

Ultimately, the decision to proceed would go to Bales. With both Armstrong and Aldrin, as well as mission control and almost the entire world watching at home, Bales would confirm “GO!” to which Charlie Duke (in the control tower) relayed to the astronauts:

Eagle, you are GO for landing!

As the alarms kept flashing Bale was again asked for further confirmation to which he would snap back “Go, Just Go!”

At this point, approximately 1300 feet above the lunar service, the landing module would begin the final phase of its landing. It was at this point, with all of his experience as a pilot at the ready, with Aldrin operating completely in synch with him, hundreds of thousands of miles away from Earth and approaching an alien world, that Armstrong took over the controls and proceeded to land on the moon.

The Landing Of The Eagle

The two astronauts had performed what felt like endless simulations of this landing run. So much so, that when they peered out of the triangular windows of the landing module, they could tell that they were still off course. In fact, they were over four miles past their target location.

Armstrong, realizing he would not have an opportunity to circle around back to the intended location, began to study the gray, rocky surface below. At first, he spotted a crater with multiple boulders and rocks around it and considered landing there, especially as they would be able to obtain samples of the rocks after stepping outside the craft. He would, though, decide against it, declaring to himself to be too risky for a smooth landing.

With their altitude decreasing by the second, Armstrong eventually spotted a flat part of the lunar surface. He headed straight for it. There was at this stage only around 90 seconds of fuel left. Once the landing fuel was exhausted, the landing module would simply drop to the surface as a dead weight resulting in the almost certain death of the astronauts.

Armstrong would use almost every bit of that fuel as the lunar surface rushed toward them unforgivingly, finally touching down with no time to spare. At mission control, despite their computer systems and readings telling them the landing had been a success, each person remained silent awaiting that confirmation from the astronauts themselves.

Duke radioed to the lunar module, “We copy you down Eagle!”

Three seconds later, Buzz Aldrin replied “Houston…” and then went silent as he and Armstrong checked and rechecked their own readings in the module. Then, came Armstrong’s voice:

Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!

Duke acknowledged the confirmation as mission control exploded with cheers and applause. In homes around the world, those watching did likewise, aware of the truly historic moment they were witnessing. Humans were literally about to walk on the moon.

“One Small Step…”

Armstrong and Aldrin would spend over six hours in the lunar module before finally stepping outside to explore their surroundings, going through checklists and other important procedures. Until then, each peered out of the windows every now and then at the awaiting desolate yet beautiful environment under an endless, rich black sky.

Writing in the book Moon Shot: The Inside Story Of America’s Apollo Landings by Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton, and Jay Barbree, they describe perfectly the location of the Apollo 11 landing and how it appeared to the astronauts in the landing module when they write:

Two days from Earth Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had landed on a ghost world – a land that had never known the caress of seas. Never felt life stirring in its soil. Never known a leaf to drift to its surface. No small creatures to scurry from rock to rock. Not a single blade of grass. Not even the slightest whisper of a breeze. They were on a world where a thermonuclear fireball would sound no louder than a falling snowflake. [2]

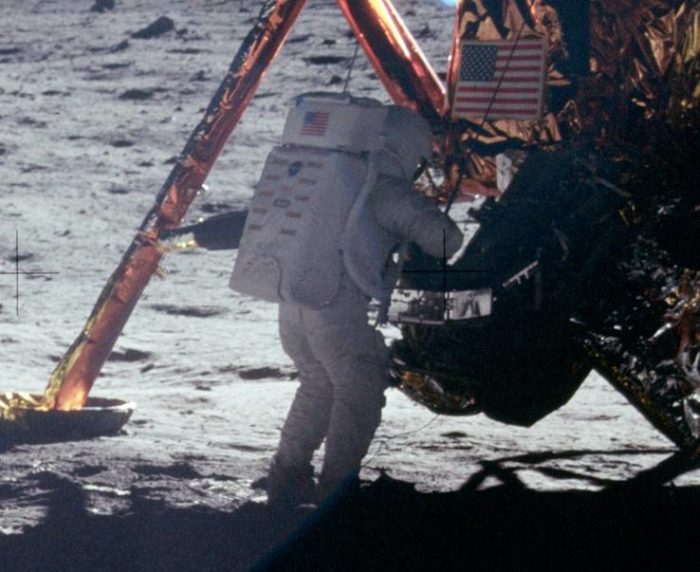

Finally, following extended delays, at just before 11 pm (United States Eastern Time) Neil Armstrong began his short but historic step down the ladder of the Eagle landing module. Back on Earth millions of people around the world watched with anxious excitement on their television screens, the live pictures being captured by a camera on the outside of the Eagle. When he was a little over three feet from the surface he jumped gently from the ladder and landed on the lunar surface. He would take a small step and then make what is perhaps one of the most famous statements in history:

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind!

Armstrong would begin examining his alien surroundings. He was alone on the surface for around 15 minutes before Aldrin was given permission to leave the Eagle and join him.

Collecting Samples In “Beautiful, Magnificent Desolation!”

As well as obtaining samples of the surface, including rocks, the two astronauts began testing how easy or difficult it was to move around in lunar gravity, which was around one-sixth of that of the Earth. They would determine that it was far easier than it had been in the simulations, almost as if they were floating.

They also examined closely the surface below them. Armstrong would describe this surface as “fine and powdery” before elaborating that it “adheres in fine layers, like powdered charcoal, to the soles and sides of my boots”. The astronauts also managed to capture multiple pictures from their location.

Perhaps the most famous moment of the astronauts’ time on the moon (aside from Armstrong’s first step) was the planting of the American flag. This was something that they found far more difficult than they had imagined. This was due to the hard lunar surface which prevented the pole from being wedged fully into the ground. However, once Aldrin had steadied the flag, he stood back and saluted it, with Armstrong capturing a picture of the moment.

After setting up various equipment on the surface for future experiments, leaving plaques on the surface (one to record their arrival and another in memory of the astronauts and cosmonauts who had died in the chase of this eventual achievement) and collecting as many surface samples as they could, they began to run through checklists once more to ensure all of their tasks were complete.

As they did so they continued to describe to mission control and the television audience what they were looking at and investigating. Aldrin, for example, would describe the moon as “beautiful, magnificent desolation”, noting how the many shades of grey contrasted greatly with the solid blacks of shadows.

They would pack their samples in specially designed sealed containers and then transferred them to the landing module. A little over two hours since Armstrong first set foot on the surface, the two astronauts pulled themselves into the landing module and sealed the hatch shut.

They each had orders to sleep for the next five hours so they were refreshed when they blasted off from the moon’s surface to dock with Apollo 11. However, a combination of exhilaration of what they had just experienced and the coldness of the Eagle itself, neither managed to sleep properly, if at all.

In total, including their time in the Eagle itself, Armstrong and Aldrin spent 21 and a half hours on the surface of the moon before blasting off from the lunar surface, leaving the launch platform and other debris behind them as they rejoined the Command Module, a journey that itself would take over three hours. Once more, Armstrong’s masterful piloting skill ensured a perfect link-up.

They would transfer themselves as well as the multiple samples they had taken into the main command module before ejecting the Eagle to orbit the moon. From there, Apollo 11 set off on the two-and-a-half-day journey back to Earth.

From The Moon Into Quarantine

On the afternoon of 24th July – four days after landing on the moon – Apollo 11 hit the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Initially, the craft landed in the water the wrong way up leaving the astronauts upside down in the water for around 10 minutes. However, when flotation bags were activated by the crew the capsule righted itself and a short time later a hovering US Navy helicopter would attach a sea anchor to the craft which kept it right where it was as they awaited pick-up. Divers would then approach the capsule and begin preparations for retrieving the crew.

Because they had been physically on the lunar surface – an alien world, remember – there was concern that if there were pathogens on the moon the astronauts could potentially bring those back to Earth. And these speculative pathogens could then, in theory, pass throughout the population. Although this possibility was considered extremely unlikely, all precautions were taken by NASA and the astronauts would be placed into quarantine.

Before they even left the floating capsule, biological isolation garments were passed to them for them to wear before exiting. Once they were on board the navy vessel, they were placed into isolation in the Mobile Quarantine Facility where they would remain until 10th August. Three days later, the three astronauts would take part in their famous ticker-tape parades. Their mission had made good on Kennedy’s promise to land humans on the moon before the end of the 1960s.

The video below contains news reports and footage of this momentous occasion.

A Few Further Points Of Interest

There are a few last points of interest to examine regarding the Apollo 11 moon landing mission. For example, contrary to how history unfolded, many of those awaiting the historic moment at the time fully expected Buzz Aldrin [3] to be the first person to step foot on the moon. The main reason for this was that during the Gemini program, the person who guided the vehicle down sat on the right-hand side of the vehicle – the side where the hatch was also located. This meant, in theory, they would be the first person out of the craft.

However, the hatch on the landing module was on the left-hand side, where Armstrong sat. This would have meant, if Aldrin was to be the first man to the Moon’s surface, he would have to climb over Armstrong, complete in his bulky space suit in order to do so. And when this was tried in trials in the run-up to the mission, there was considerable damage done to the module. Perhaps swinging it fully in Armstrong’s favor was that there was an apparent preference for Armstrong to emerge first purely as he was the commander of the craft.

For their parts, Armstrong claimed he was “never asked his opinion” on the matter, while Aldrin would state it was “fine with me if it was to be Neil”.

Regardless of who stepped foot onto the Lunar surface first, a particularly interesting and respectful gesture discreetly took place before Aldrin and Armstrong left the moon and prepared to set off to Earth, they left medals [4] once belonging to Yuri Gagarin (who had died the previous year) and Vladimir Komarov (who died during re-entry attempt in April 1967). The medals had been given to the NASA astronauts by fellow astronaut, Frank Borman, who received them from the widows of the two cosmonauts who wished them to be placed on the Lunar surface.

This is perhaps another sign of the underlying respect and desire for cooperation from those on both sides of the Space Race – opposing sides that were used whenever possible by their respective governments and ideologies.

With that said, however, there was always room for potential propaganda, it would seem. And it is with that in mind that we turn our attention to the Soviet Luna 15 mission, which took place, coincidentally or not, at the same time as the Apollo 11 landing mission.

The Luna 15 Mission – An Attempt to “Upstage” The Apollo 11 Landing?

Although it wasn’t a concern to many in the United States at the time, a Soviet mission to the moon [5] was taking place at the same time as the Apollo 11 moon landings. Whether the Luna 15 mission was purposely designed to take some of the potential glory away from Apollo 11 mission or not is perhaps open to debate.

An article in the International Herald Tribune [6] on the 23rd July 1969 stated that the Luna 15 was regarded by many of those who had followed the planned mission as an attempt by the Soviet Union to “land on the moon, pick up some rock samples, and ‘race’ Apollo (11) back to earth in an effort to upstage the American effort”.

The original plan was for the Luna 15 spacecraft to land on the moon approximately two hours before the proposed landing of the Apollo 11, collect lunar soil from the surface and return it to Earth for study (the second attempt at such a mission). However, when they finally entered lunar orbit, the unknown terrain below caused a significant delay, which may have been due to a mid-course correction shortly after it set out to its destination.

According to Neil Armstrong, the Apollo 11 crew were unaware of the Luna 15 mission [7] when they set off on their historic journey. He would recall that they were only informed of the Soviet craft once they were well on their way to moon.

Despite the Apollo 11 crew, like most Americans, being unaware of the Luna 15 mission, NASA was fully aware of the Soviet’s plans and activities. In fact, NASA and the Soviet Space Program had even gone as far as to share in full the flight plans of their respective missions, essentially to avoid a collision in space which would almost certainly kill the Apollo 11 astronauts. The Soviets also ensured they would be far enough away from NASA’s planned landing site so as to avoid interfering with the Apollo 11 mission.

Despite alleged attempts to beat the Americans in terms of returning samples of the Moon back to earth, the delay meant that by the time the Luna 15 began its descend to the Lunar surface, Armstrong and Aldrin were already there and exploring it on foot. What’s more, it appeared that the unmanned craft had crashed into the Moon as opposed to landing on it.

Although further information would come to light years later, the newspaper report in the International Herald Tribune stated three days after the landing attempts how the Tass news reports “which often carries rather flowery tributes to the ‘success’ of Soviet space missions” had not done so for the Luna 15 mission. Further according to the newspaper report, all that was mentioned by Tass was that “the program of research in the space near the moon and of checking new systems of the automatic station Luna 15 was completed”.

In the summer of 2009, an audio recording of the landing attempt [8] was made public. The recording had been made by scientists at the Jodrell Bank Observatory at the Jordell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester in the UK, who managed to listen in to the Soviet Luna 15 mission. What’s more, Sir Bernard Lovell – the founder of the observatory – narrates what is taking place during the landing attempt.

He would describe it as “drama of the highest order”, before informing the potential listener that “it’s landing” and “it’s going down much too fast”.

It is perhaps worth mentioning that data captured at the observatory had been used by NASA for their space missions since the late 1950s, including for the Apollo 11 mission. It had also been used to monitor the Soviet Union’s space missions, particularly so after their early successes which saw them firmly ahead in the space to reach the stars.

Even more intriguing, and an alarming reminder of the environment of the Cold War, was that Lovell revealed around the same time the recordings were made public that there was an attempt assassinate him using a “lethal radiation dose” while he visited a Soviet space facility in the early sixties.

Incidentally, it is largely believed by scientists and experts who have studied the Luna 15 data that even if it had have recovered samples of the Lunar surface and successfully set off back to Earth, it almost certainly would have been too slow to beat the Apollo 11 craft back to home.

You can listen to that recording below.

A Truly Historic Moment

There would be several more Apollo missions over the coming years, which we will examine in detail in an upcoming article. However, for various reasons, these missions were suddenly pulled, despite having already been budgeted and passed. Initial thoughts of creating a permanent residency on our cosmic neighbor were seemingly cast aside, with no crewed missions taking place after 1972.

Even so, the moon landing of July 1969 remain one of the most historic moments of the twentieth century.

However, the exploration of space would continue. And for the 1970s and 80s, it would continue under the umbrella of the Cold War. However, following the moon landings, there was now much more cooperation between the two ideologically opposed nations. And some of the achievements that would follow the moon landings have not only encouraged cooperation between nations but also have advanced life for many here on Earth. There was, though, a recognition that NASA and the Americans were seemingly the dominant nation in space

Perhaps we should consider for one moment if the Apollo 11 moon landing mission had gone wrong. What if it had been aborted at the last moment, or worse still, if the landing module had crashed into the lunar surface killing Armstrong and Aldrin? Would further attempts have gone ahead or would the program have been abandoned entirely, unfulfilled? Might the Soviet Union have taken the opportunity and beat the United States to the moon? One thing is for certain, if the Apollo 11 mission had gone any other way, the history that would have unfolded in the aftermath would be drastically different than what we know today.

The video below looks at the early Apollo missions and the historic moon landings in a little more detail.

References

| ↑1 | “Live from Cape Canaveral”: Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to Today, Jay Barbree, ISBN 9780061 735899 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America’s Apollo Moon Landings, Alan Shepard, Jay Barbree, and Deke Slayton, ISBN 9781453 258262 |

| ↑3 | Choosing The First Man On The Moon, NASA, History https://history.nasa.gov/SP-350/ch-8-7.html |

| ↑4 | The Apollo 11 Astronauts Left A Lot Of Junk On The Moon, Kiona N Smith, Forbes, June 20th, 2017 https://www.forbes.com/sites/kionasmith/2017/07/20/the-apollo-11-astronauts-left-a-lot-of-junk-on-the-moon/?sh=56847b4e4ca0 |

| ↑5 | Luna 15 Accompanied Apollo 11 to the Moon, Amy Shira Teitel, Discover Magazine, July 5th, 2019 https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/luna-15-accompanied-apollo-11-to-the-moon |

| ↑6 | 1969: Soviet Spacecraft Reaches Moon, but Crash Landing Is Suspected, International Herald Tribune, July 23rd, 1969 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/23/world/europe/luna-15-soviet-moon.html |

| ↑7 | 50 Years Later: Soviet probe raced Apollo 11 to the moon, David Kerley, Mina Kaji, and Samantha Spitz, ABC News, July 18th, 2019 https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/50-years-soviet-probe-raced-apollo-11-moon/story?id=64404137 |

| ↑8 | Recording tracks Russia’s Moon gatecrash attempt, Jonathan Brown, The Independent, October 23rd, 2011 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/recording-tracks-russia-s-moon-gatecrash-attempt-1730851.html |

Fact Checking/Disclaimer

The stories, accounts, and discussions in this article may go against currently accepted science and common beliefs. The details included in the article are based on the reports, accounts and documentation available as provided by witnesses and publications - sources/references are published above.

We do not aim to prove nor disprove any of the theories, cases, or reports. You should read this article with an open mind and come to a conclusion yourself. Our motto always is, "you make up your own mind". Read more about how we fact-check content here.

Copyright & Republishing Policy

The entire article and the contents within are published by, wholly-owned and copyright of UFO Insight. The author does not own the rights to this content.

You may republish short quotes from this article with a reference back to the original UFO Insight article here as the source. You may not republish the article in its entirety.

1 Comment

UFO Insight does not take responsibility for the content of the comments below. We take care of filtering profanity as much as we can. The opinions and discussion in the comments below are not the views of UFO Insight, they are the views of the individual posting the comment.

Newest comments appear first, oldest at the bottom. Post a new comment!

**** thrilling …. too good …..enjoyed reading it so much…