The Handshake In Space – The Apollo-Soyuz Project

- By

- January 16, 2021

- September 29, 2021

- 10 min read

- Posted in

- Space, History

Following the shutting down of the Apollo program, attention turned to the creation of a space station. However, there was also the realization – perhaps especially due to the near misses and tragedies (on the Soviet side) – that each space program could benefit from working with the other.

This was perhaps first demonstrated – at least publicly – in the summer of 1975 when the Apollo-Soyuz Project (officially called the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, or ASTP) came to fruition, a mission that would see the United States and the Soviet Union perform a “handshake” in space by docking their vehicles together while in orbit.

The main aim of the mission was to show that each nation could come to the aid of the other should either side run into trouble in space. However, on a deeper level, it showed that the hard, dismissive attitudes of the Cold War were starting to thaw significantly. And while it would be a further decade and a half before the end of the ideological conflict with the breaking up of the Soviet Union, this mission in space, watched by millions of people around the world had seemingly planted the seeds of change on Earth.

Indeed, the Apollo-Soyuz mission is perhaps another example of the often-overlooked importance, influence, and benefits of our collective desire to explore the great unknown of the universe.

Contents

- 1 Following The End Of The Apollo Missions

- 2 The Groundwork For The Handshake In Space

- 3 The Other Side Of The Desire For Cooperation

- 4 From The Soviet Perspective

- 5 “We’ll Be Up There Shortly!”

- 6 Handshakes In Space

- 7 A Potentially Tragic Apollo End, Narrowly Avoided

- 8 The Lasting Importance And Legacy Of The Handshake In Space

Following The End Of The Apollo Missions

Following the successful Apollo 17 mission the Apollo program came to an end – at least as far as missions to the moon were concerned. However, with the shuttle missions still half a decade away, there was still a use for the Apollo craft. And one of the most high-profile of these would be the Apollo-Soyuz mission – an extension of the Détente period of the Cold War.

Perhaps to put the situation into perspective a little, we should turn to the book Live From Cape Canaveral: Covering the Space Race from Sputnik to Today by Jay Barbree, which states:

On the fifteenth day of July 1975, according to the best intelligence available, some 200,000 rockets built for war were in the arsenals of the United States and the Soviet Union… Never in history had our planet been so threatened by its dominant species. [1]

At the same time, “two of those rockets carried humans instead of means of destruction”, and with them, they carried hope for a future world that would eventually see a climbdown from the constant on-the-precipice of all-out nuclear war feeling of our collective existence. The Apollo-Soyuz mission was perhaps a symbol of that hope.

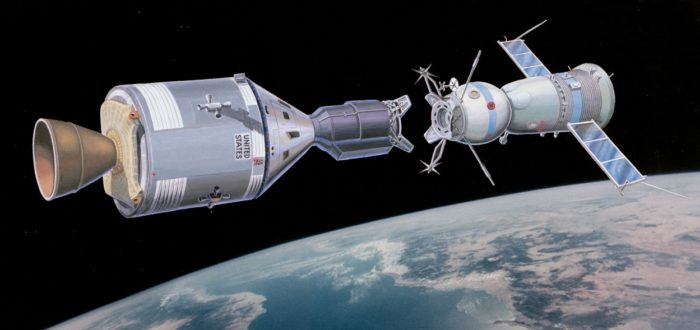

Artist’s impression of the Apollo and Soyuz 19 docking

Of course, the mission was years in the planning before it finally came to fruition. In reality, the moment Neil Armstrong stepped on the moon – at least from an engineer, scientist, and cosmonaut perspective – there was no other direction to go than to work together.

And while these feelings of potential cooperation for the greater good were largely kept within tight circles away from government officials (who very much continued to officially ignore the achievements of NASA and the United States), when they eventually got the opportunity to work with their American counterparts, most were more than willing and ready to do so.

Much the same, we should note, can be said for those on the American side of the divide, perhaps an example that the Cold War-like any other conflict, ideological or otherwise, are largely battles of the few at the top and not those of the general populations.

The Groundwork For The Handshake In Space

There had been, of course, efforts made in the early 1960s to bring about more cooperation and peaceful existence between the United States and the Soviet Union when communication between President Kennedy and the Soviet Premier, Nikita Khrushchev led to the Dryden-Blagonravov agreement. This agreement promoted the sharing of data from each of the country’s missions into space. However, following Khrushchev’s departure and Kennedy’s assassination (in 1964 and 1963 respectively) any further cooperation essentially ceased.

However, with the much-anticipated withdrawal of the American military from the Vietnam conflict, talks began in the summer of 1971 about the possibility of a joint mission into Earth’s orbit. These talks – between engineers from both sides of the ideological divide – would take place in Houston and Moscow, giving each side the opportunity to inspect the inner workings of the others’ space program. And there were many differences to iron out – even at an engineering level.

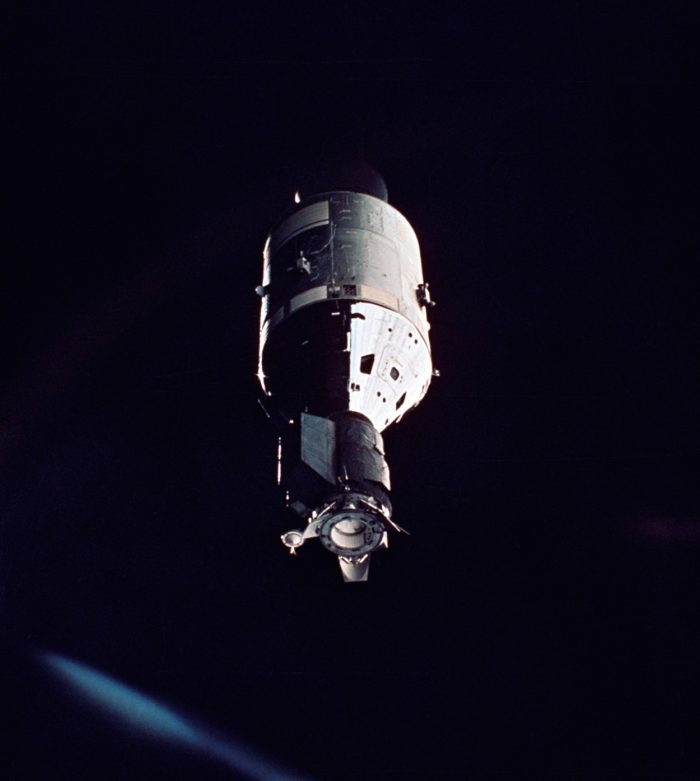

The Apollo as viewed from the Soyuz 19

For example, despite the Soviet Union initially taking the prominent position in the Space Race, as well as the perspective of the Americans right up to the actual moon landings that their counterparts were much further ahead than they were, NASA engineers considered the Soviet Soyuz vehicle primitive by comparison to the Apollo craft.

From the NASA perspective, there were far too few options for the cosmonauts while in flight. If there was a problem, the mission would essentially be canceled and the craft would return to Earth, with very little (relatively speaking) for the cosmonauts to do as far as decision making or actual piloting.

NASA missions, on the other hand, generally gave much more control to their astronauts. And as had been demonstrated most predominantly with the Apollo 13 mission, they allowed their astronauts to react to the situation they might find themselves in and then use their extensive piloting skills accordingly. By contrast, the Soviet engineers considered the lack of options for their cosmonauts reduced the risk of human error and was ultimately safer. They even labeled the Apollo “dangerous” and “complex”.

Despite this, though, the talks would lay down the foundation of the Apollo-Soyuz mission.

The Other Side Of The Desire For Cooperation

It is very much worth mentioning that despite the hope of further cooperation – and perhaps even an end to the Cold War – many people were not only not as enthusiastic but were actively against such cooperation.

For example, given that the Apollo was clearly the more advanced vehicle of the two, as well as the recent achievements of NASA and the Apollo moon landing missions, some American commentators believed the mission would result in a distorting of history and grant the Soviet space program more credit than they deserved for the mission. Even worse, such commentators feared, this would result in the Soviet space program being placed on a plateau similar to that which NASA currently resided. These fears have obviously proven to be wide of the mark, but it perhaps underscores the intensity of feeling in many Americans about the Soviet Union.

The Soyuz 19 as viewed from the Apollo

Others worried about the obvious (and perhaps understandable) risk of espionage the mission would present. Others still, claimed that the success of such a mission would even make the average American citizen become too trusting of the Soviet Union, and perhaps even their ideology. Indeed, authorization from Congress for various stages of the eventual mission faced considerable pushback.

There is no doubt that like the average American of the times, many Soviet officials and citizens were equally generally suspicious of the United States. However, unlike the trouble to have the project authorized experienced in America, no such problems reared their head in the Soviet Union. Whether for propaganda purposes or not, the Soviet rhetoric was that despite their differences, scientific cooperation between the two nations was of more importance, something which painted the American critics as attempting to block such progress, and essentially, as the “bad guys”.

The reality of the situation is perhaps that aside from the most ardent supporters on each side of their own ideology, most people were beginning to desire more cooperation between the two super nations of Earth, perhaps realizing the true importance of such cooperation.

From The Soviet Perspective

Unlike previous Soviet space missions, the Apollo-Soyuz mission (named the Soyuz-Apollo mission from the Soviet perspective) would be played in full view of the public for the first time – including their own people.

What’s more, Soviet officials granted American astronauts and engineers access to their facilities and the Soyuz 19 itself.

It was beyond doubt to the Soviet Union, despite their occasional public stance, that the United States was very much further ahead in the efforts to reach into space. And while they perhaps hoped that their own space missions might one day stand on their own and rival the achievements of NASA, there was a growing consensus that cooperation with the American space program would ultimately benefit their own ambitions.

With the cameras of the world pointed at the launch pad in Kazakhstan on the afternoon of 15th July 1975, the Soyuz 19 prepared to begin its historic journey – a journey that the Soviet politician, Leonid Brezhnev correctly labeled the “first major joint scientific experiment in the history of mankind”.

As the Soyuz 19 reached up into the heavens and the endlessness of space, the world watched on television. The Apollo astronauts who would make up the other half of the mission, meanwhile, were asleep in their beds, waiting to be given the call to being their final preparations.

The video below features the launch of the Soyuz 19.

“We’ll Be Up There Shortly!”

On American territory, the astronauts were awoken with the message that “your friends are upstairs. Right on schedule”. With that, Tom Stafford, Deke Slayton, and Vance Brand knew it was their turn to prepare for launch. Now, all eyes were on the Kennedy Space Center in Florida for the Apollo side of the mission.

By the time the Apollo craft was ready for liftoff, the Soyuz 19 was just about to complete its fourth orbit of the planet. Before launch, Stafford would communicate with the Soviet cosmonauts, informing them that they would “be up there shortly”.

Moments later the Saturn 1B rocket began to lift the last Apollo vehicle that NASA had off the ground. The launch would be textbook and minutes later the Apollo craft was in Earth orbit. After taking a moment to appreciate their surroundings and adjust to the weightless environment of space, the astronauts changed into their flight coveralls and then informed their Soviet friends that they were with them orbiting the planet. They would then begin the process of tracking down the Soyuz 19 – a mission in itself that took two days.

The Apollo was in a lower orbit than the Soyuz 19, however, Stafford used his considerable piloting skills to perform course-correcting thruster burns that eventually brought the Soviet vessel into range. As the two space crafts were orbiting over the city of Metz in France, Stafford brought the Apollo toward the bright green Soyuz 19 and prepared to dock with it.

Because each of the respective space program’s craft had different docking mechanisms, in order to make the docking possible, the Androgynous Peripheral Attach System (APAS) had been developed (by Bill Creasy). One of these would be fitted to each craft’s docking system and was designed so that each craft could be “active” or “passive”.

Now, with Stafford carefully bringing the Apollo to the Soyuz 19, that docking mechanism was about to be tested for real. The docking went perfect as Stafford informed the control tower, and in turn, the watching world below them, “we have capture!” From the Soyuz, Leonov would offer his congratulations to Stafford, claiming the “Soyuz and Apollo are shaking hands”. Shortly after, the crews themselves would meet and replicate this handshake.

Handshakes In Space

Following the successful docking of the two space crafts, the crew on each side went to work preparing to unlock their respective hatches and float into the tunnel that connected their ships. When they did, Stafford and Leonov went first, each reaching out eventually shaking hands and congratulating the other on their achievement.

Stafford uttered the word “friend” while Leonov replied that he was “very happy to see” him. Stafford and Leonov would become firm friends following the mission, a friendship that lasted until Leonov’s death in October 2019.

The short video features news footage of the historic moment.

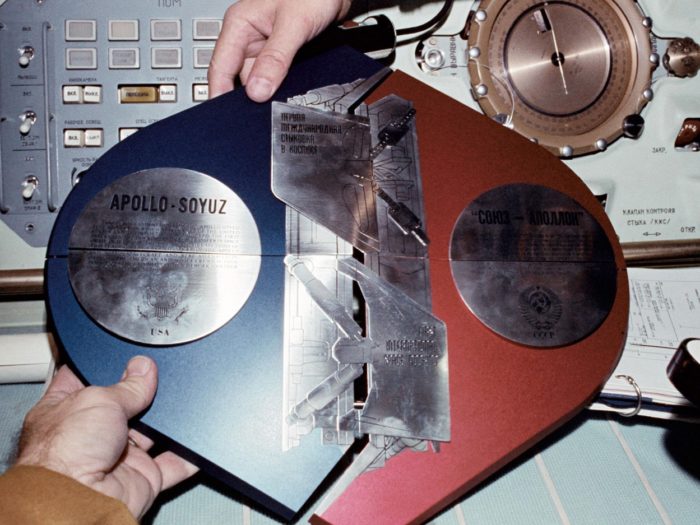

The rest of the crews followed as the world watched on their television sets below. The crews exchanged various gifts and symbolic writings and plaques before they all proceeded to enter the Soyuz itself where they would sit down to eat. The crew of the Apollo would play host to a second meal later in the mission.

Each crew would take the other on full tours of their ships, both of which were documented for television.

In total, the two ships were locked together for just short of two days, with the crews performing several scientific experiments during this time. They would also exchange tree seeds from the native countries so that they could be sown in the other once returned to Earth (which they ultimately were).

The handshake between Stafford and Leonov

Before the final unlocking, the Apollo craft separated from the Soyuz and put itself into position so they could create an artificial solar eclipse which the crew of the Soyuz photographed (allowing them to capture the Sun’s corona). The two ships would redock for several more hours before they finally separated and went about the final parts of the respective missions.

Incidentally, the crews from the Apollo and Soyuz 19 would meet in Moscow several months later in September 1975 as part of a goodwill visit and tour of the Soviet Union by the Apollo astronauts.

A Potentially Tragic Apollo End, Narrowly Avoided

The Soyuz would reenter the Earth’s atmosphere two days after the separation while the Apollo craft did so three days after that. When they did so, though, their reentry almost resulted in a tragic event.

Following their five days orbiting the Earth after unlocking from the Soyuz, the Apollo craft would reenter the Earth’s atmosphere ready for splashdown. Due to the cacophony of sound and noise during the reentry, Brand failed to hear Stafford call the Reaction Control System to be shut off. As this was left open, toxic fumes were able to infiltrate the cabin. And these fumes were extremely dangerous – so much so that Brand would temporarily blackout.

Stafford’s quick acting was key. He would quickly reach for the emergency oxygen masks on board, and after placing one on Brand, made sure he and Slayton were secure and safe from the fumes. We can only imagine the aftermath of the mission if Stafford hadn’t acted as quickly as he had, and the three astronauts had been discovered dead in the Apollo following splashdown.

They would ultimately experience no further problems, although each of them would spend two weeks recovering from the experience in the hospital.

With the recovery of the three astronauts, the Apollo program was now a thing of the past.

The plaques exchanged during the mission

Although the Apollo program would cease to operate following the Apollo-Soyuz mission, the Soyuz missions would continue, in the form of “generations” of Soyuz spacecraft right up until the modern era. Incidentally, we will examine the Soyuz space program in more detail in a future article.

Various experiments were undertaken during these Soviet space missions, including docking with the Salyut space station (a program we will also examine further in an upcoming article) and the exposure of living organisms in space for several months at a time.

In total, the second-generation Soyuz spacecraft (of which the Soyuz 19 that docked with Apollo was a part), would remain active until 1981 with Soyuz 40 being the final mission.

The Lasting Importance And Legacy Of The Handshake In Space

The importance of the Apollo-Soyuz mission can’t be understated. As we mentioned in the opening, it was perhaps the first truly solid, if symbolic, moment of what such cooperation could achieve, as well as that each nation could coexist peacefully despite their differing political outlooks.

Speaking decades later, [2] Tom Stafford would state that he imagined people at home watching the historic handshake with Leonov and thought “if people like this can work together we can work together on a lot of things”.

We should note that as real as the desire for cooperation in space was, each side of the divide continued to overplay their own importance, both to their own populations and the world. And it is true that a slowing down in the eagerness for joint missions did occur in the years that followed the Apollo-Soyuz mission.

Indeed, while the handshake in space is seen by most to be the event that brought the Space Race to an end, each nation still pursued its own interests. However, unlike the previous years where such propaganda was used to instill a fear of each side, each nation’s space missions took on a feeling much more in line with healthy competition. And while the end of the Cold War was still a decade and a half away, the seeds of such cooperation were very much sewn.

In the same interview highlighted above, Leonov would state that “these (missions) were the best competitions, higher than the Olympics, because as a result of this, as you call it a race, we developed brand new equipment that we’re still using today”.

Although it was a slow burn of continued collaboration, following the demise of the Soviet Union the United States and Russia began regular joint space missions together in space, with American astronauts regularly taking part in such missions on the Mir Space Station. These missions would ultimately lead to joint missions between the two countries (along with many others) on the International Space Station. All of these international collaborations, however, started with the Apollo-Soyuz mission of 1975. And for that, its importance should be recognized.

The documentary below examines this historic space mission in a little more detail.

References

| ↑1 | “Live from Cape Canaveral”: Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to Today, Jay Barbree, ISBN 9780061 735899 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | How historic handshake in space brought superpowers closer, Kellie Morgan, CNN, July 15th, 2015 https://edition.cnn.com/2015/07/15/world/space-handshake-anniversary/index.html |

Fact Checking/Disclaimer

The stories, accounts, and discussions in this article may go against currently accepted science and common beliefs. The details included in the article are based on the reports, accounts and documentation available as provided by witnesses and publications - sources/references are published above.

We do not aim to prove nor disprove any of the theories, cases, or reports. You should read this article with an open mind and come to a conclusion yourself. Our motto always is, "you make up your own mind". Read more about how we fact-check content here.

Copyright & Republishing Policy

The entire article and the contents within are published by, wholly-owned and copyright of UFO Insight. The author does not own the rights to this content.

You may republish short quotes from this article with a reference back to the original UFO Insight article here as the source. You may not republish the article in its entirety.